Chapter 3.

Shot Down

Why were POWs in Hiroshima?

One of the reasons why Hiroshima was selected as a target candidate for dropping the Atomic Bomb, according to a US document, was “There is no POW camp in Hiroshima”. Technically, there should have been no POWs in Hiroshima. However, perhaps fate played a trick on human beings as the POWs had been brought to this city. If there had been a slight difference in the date of their capture, or if they had been captured as POWs elsewhere, their fate might have been changed. In the first place, how did the US military POWs arrive in Hiroshima City? How did they become POWs and how is it that they were taken to Hiroshima?

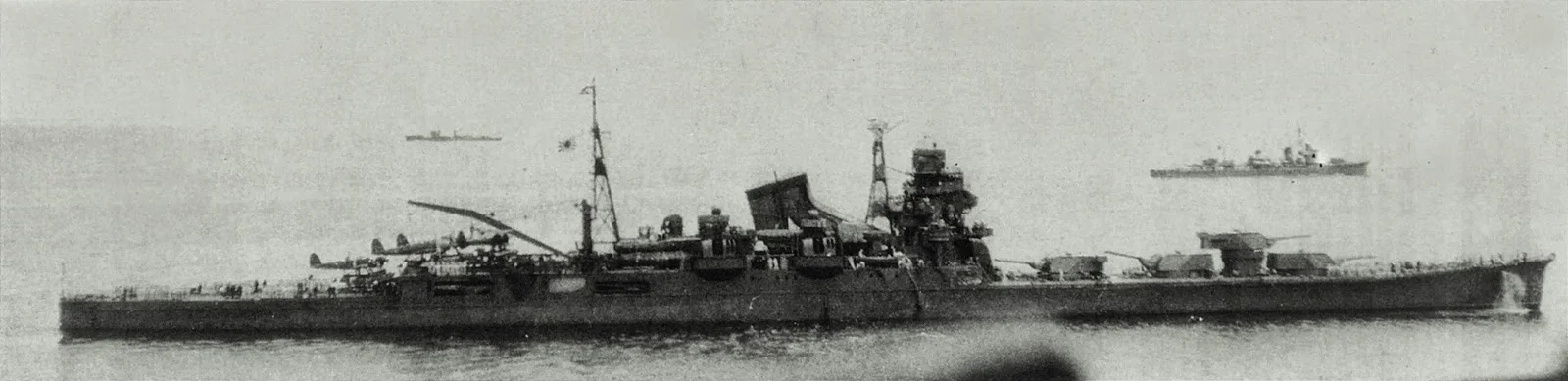

Japan's nearly indestructible Fast Battleship Haruna.

I believe that the Japanese battleships that played the most pivotal part in the war against the US were neither the Yamato nor the Musashi, but the Kongo or the Haruna. For the US military, these two were the most detestable war vessels. In Guadalcanal, the two ships fired hundreds of shells into the Anderson Airfield, which originally was constructed by the Japanese, making the blood of the US soldiers run cold. The Haruna, which had given a display of how dreadful the naval bombardment could be, returned from the southern sea and was moored in Kure Harbor after the sea-battle off Leyte. On March 19, Kure became the first target of the air raids by the Allied Forces. On this occasion, a bomb that was dropped by an enemy carrier plane hit the Haruna, killing twenty-four crew members. In April, when the Yamato was ordered to make a sortie to Okinawa, the Haruna provided the Yamato with all the heavy oil fuel she had; therefore, the Haruna was not going anywhere. On June 22, the Haruna was again attacked by B-29s, and a bomb hit the stern.

The Japanese Navy determined that it was risky to have all the war vessels gathered in Kure Harbor; therefore, it implemented a campaign of scattering the vessels around different parts of the islands, camouflaging them by planting trees such as pine or cedar on the decks. The Haruna also was dispatched from the quay of the Kure Naval Arsenal, and was towed by a tug to Koyo, a harbor on Etajima Island within Hiroshima Bay, which is part of the Seto Inland Sea. Kure repeatedly was air raided. The bombing targets were the ammunition factories around the Kure Naval Arsenal and the streets of Kure City. More than ten of those war vessels such as carriers, battleships, cruisers, and destroyers, were moored, all camouflaged, in different locations around the islands in Hiroshima Bay.

Japanese Heavy Cruiser Tone, 1942. The Tone was towed to Etajima where it was used for training (viz.wikipedia).

Hyuga sunk off Kure.

Finally came the events of July 24 and 28. There was massive fighting on those two days, which is called the last of the Sea and Sky Battles between the US and Japan. There were numerous carriers, battleships, cruisers, destroyers and submarines in Kure. There were aircraft carriers––the Katsuragi, the Amagi, the Ryuhoh, and the Aso; battleships––the Haruna, the Hyuga, and the Ise; cruisers––the Izumo, the Iwate, the Aoba, the Tone, and the Oyodo; destroyers––the Tsubaki, the Tokitsukaze, and the Tanikaze; and submarines including six large “I-go” Dai-ichi Submarines, and one small “Ro-go” submarine. All of the vessels were camouflaged. However, the US Forces took aerial photos and had looked thoroughly at the shapes of the vessels. “Sink all the Japanese war ships leaving none of them,” ordered Admiral W. F. Halsey, Commander of 3rd Fleet. The combined American and British military forces devoted all their energies to attacking the Japanese Naval vessels that were outside Kure Harbor on July 24, sinking most of them. However, it was impossible from the aerial photos of the vessels to tell if they had actually been sunk or were simply grounded. Therefore, the order of assault was issued again, which was the attacks on July 28.

The heavy cruiser Tone, exposed to bombardment by the US Navy aircraft carrier planes on July 24, 1945. The crew is firing antiaircraft weapons, and she is surrounded by great geysers caused by the close-falling bombs. The air attack was repeated on July 28, and the Tone sank with serious damage.

The Haruna under attack by the US Navy while moored off Etajima, the site of Japanese Navy's "Annapolis".. Her 4-10 inch armor saved her from several other attacks, including direct strikes by 500-lb bombs.

Early on July 28, 37th British Task Force and 38th US Task Force, which were both off Kochi of Shikoku Island, launched all the able carrier planes, one after another, and assaulted the Haruna and the Tone, which launched a counterattack. The enemy attack was primarily focused on the Haruna, and from 8 a.m. onward for the full morning, bombing went on without interruption. In the afternoon, B-24s that flew from Okinawa joined the action. Following the lead plane, thirty-three planes dropped 2,000 pound bombs, sending up water sprays surrounding the Haruna that were several times higher than the ship. During the fight in the morning, the Haruna defended against the 240 or 250 US carrier planes with machine guns. Seven or eight of the US planes were shot down, sending smoke into the air. The planes crashed into the sea or mountainsides near the island and burned up. In the afternoon, against the B-24s, which started bombing at the height of 4,000m, the twelve anti-aircraft guns of the Haruna started shelling one after another. They fired a total of 3,000 shells at the average rate of one per twenty seconds. The Haruna’s main gun fired a new type of shell, leaving the B-24s full of scars. In the records of the US, it is written that the counterattack by the Haruna had not been expected, but her shell attacks were precise. The lead plane at the top of the formation initiated bomb release on the target. That bomber was hit and although damaged, it managed to reach Ie-jima Island. Every other plane was also hit and damaged. On the other side, the damage the Haruna received was horrible. It was directly hit by thirteen bombs, and, being seriously damaged, the bottom of the ship grounded that evening. The casualties were high. Sixty -six soldiers were killed in action on the 28th, and with mortalities on the 24th added, a total seventy-seven lives were lost. That was the last Battle of Sea and Sky in Kure, on July 28. Through the assault of the US military forces, the remaining Japanese fleet was mostly destroyed; however, through their counterattack using the best of their remaining power, the sacrifice made on the American side was never small. According to the GHQ historical records, the planes of the US Army Air Force that were shot down on that day were two large planes, the Taloa and the Lonesome Lady, and twenty carrier planes, which makes a total of twenty-two.

The Battleship Haruna, being bombarded on July 28, 1945 by the carrier planes of the US Navy, off the shore of Koyo, Etajima, where she had been moored. The crew fought back with machine guns and high-angle guns; however, by evening the ship was resting on the bottom. On this day, two B-24 bomber planes, the Lonesome Lady and the Taloa, as well as twenty aircraft carrier planes of the US Navy were shot down by the Japanese Forces.

A Japanese battleship sunk at anchorage near Kure harbor. Trees were planted to provide camouflage from high-altitude planes..

The circumstances in which the Lonesome Lady was shot down

During the period between July 28 and 30, large and small airplanes of the US attack were shot down. Two large planes were downed on land while all the small planes fell into the sea. Detailed facts regarding those incidents are provided in the Japanese police records.

U.S. Army Air Force B-24J Lonesome Lady.

Let us start with looking into the cases of the heavy bombers. The Lonesome Lady, a B-24 bomber, took off from Yontan Airfield (later Yomitan Airport) of Okinawa in a group of thirty-three planes. Usually, a formation consisted of six planes. This particular day, two planes were not airworthy and did not participate. Therefore, the formation consisted of four, with the Lonesome Lady on the left of the lead plane and the Taloa was behind the lead plane. While it was attacking the Haruna, a shell hit the Lonesome Lady. The pilot of the leading plane reported that the Japanese attack was “fierce and precise”. It was also reported that “It was the most horrible curtain of anti-aircraft firing that I had ever experienced.” Of course, it was impossible to go through this curtain unscathed. The Lonesome Lady, had just dropped three 2,000-pound bombs when it was directly hit by the anti-aircraft fire. Instantly, a fire started in the plane. Ellison, the engineer, tried to put out the fire using two fire extinguishers, but it was difficult. Instead, the fire started to grow inside the plane. The smoke that was filling the plane made it hard for the crew to breath. The pilot desperately tried to manipulate the controls to steer the plane toward the Pacific Ocean. If the plane crashed into the sea, the Allied rescue plane from the sky or the submarines in the water would find the crew, making the possibility for survival high. Seeing the dire situation in the plane, the commander in charge, Lt. Cartwright, made a decision for the crew to bail out. “Bail out!”, “Bail out!”, he commanded. To make the situation worse, the voice tube for forwarding the order was broken. He decided to have the order relayed forward and aft of the cockpit. Everyone was in a panic inside the plane. When the pilot’s order was given, the crew had gathered near the hatch with their parachutes on their back. However, the bomb-bay doors would not open. Recognizing this fact, everyone became pale. Among the screams and angry shouts, the pilot’s voice was heard. “Kick the door open!” B-24s were designed so that the door of the bomb bay could be kicked open in an emergency. Those who were in the rear section of the plane were Able, the Tail Gunner, Atkinson, the Radio Operator, and Ellison, the Engineer[1]. The other members of the crew, Pilot Cartwright, the Co-Pilot, Looper, Navigator Pedersen, Bombardier Ryan, Nose Turret Gunner Long, and Lower Ball Turret Gunner Neal were in the forward areas. The hatches, the exits of the B-24, were located both in the front and rear part of the plane.

First, when Pedersen kicked the door of the bomb bay, it opened quickly. He jumped immediately. Out of the rear hatch, Able jumped first. With the intercom knocked out it was impossible to get permission directly from the pilot-in-command. He left the plane on his own judgment[2]. His parachute opened and, looking down, he saw layers of mountain ranges below. The plane flew on, emitting smoke from the sky above Kure Harbor across the Seto Inland Sea, Otake City and Iwakuni, towards the Chugoku mountain range. Near Iwakuni along the Gantoku Rail Road, there is Hashirano Station. One of the American soldiers parachuted here. It was Able. Please remember this, because Able was the only one who was captured and not brought together with the others of the Lonesome Lady crew. After hiding in the mountains for eight days he was no longer able to endure the starvation. He saw an early morning train, and submitted himself in the train. A boy of fourteen or fifteen years old noticed his blue eyes. While he was being taken, he was beaten by a mob. As he was captured by the Navy in Tokuyama, he was held in the prison of Tokuyama. He was later sent to the Naval Prison in Kure[3], which was fortunate for him.

The American soldier who followed Able out of the bomber fell in the peaceful mountain village of Takayasu in Minami Kawachi. It was located to the north of Hashirano. The peaceful village fell into an awful confusion, as the villagers saw an American soldier parachuting down. Headed by a policeman, peasants with a sickle, a bamboo spear or even a hunting gun in their hands, were climbing up the mountain slope. The soldier who had landed, desperately ran up the slope. Eventually he was cornered and a gun fight started. The American’s shooting skill was precise, and he shot down a Japanese citizen. However, he was finally captured and handed over to the Military Police. This American soldier was Atkinson.

The order in which the crew jumped from the plane is not clear, but considering the geographical situation, the next jumper seems to have been Ryan. He was captured in Minami Kawachi Village, Kuga County, Yamaguchi Prefecture, the same area where Atkinson landed. However, he ran through the mountain forest and was captured at 17:30, July 29, the next day. He was taken to Hiroshima at 5:00 a.m. July 30, by the train from Iwakuni, and was sent to the Chugoku Military Police Headquarters.

The plane flew on and went into a spin. Several friendly planes flew close. The altitude kept dropping and mountain forests were drawing near. The fire inside had become fierce and smoke obscured everything. It was mentioned that Ellison had tried to put out the fire with the extinguisher, but by this time, the crew had given up doing so. Near Takamori, Long, Ellison and Neal jumped. One of the three was severely beaten by the civil defense unit members. Around 15:30 on July 28, all three were captured and taken to Takamori Police Station in a truck. At the Police Station, they were given rice balls, which were the size of soft balls. Without knowing those balls were food, the three started playing catch. A policeman explained to them through an interpreter that it was food, so they understood.

The last men on the plane were Second Lieutenant Cartwright and copilot Looper. Cartwright was the last to jump, and he landed near Ikachi Village, Kuga County of Yamaguchi Prefecture (current Yanai). The abandoned plane flew on a little longer, but eventually crashed nose down, caused a forest fire, and burnt down a house.

☆ The Pilot And The Copilot Who Bailed Out Last

Cartwright and Looper, were taken into custody by the Civil Defense Unit at 15:30, July 28, and were taken to Yanai Police Station. At 23:00 the following day, they boarded a train that departed from Yanai for Hiroshima where they were held in the Chugoku Military Police Headquarters.

The detailed process from the shooting down to the arrival at Hiroshima was written by Cartwright in his book, A Date with The Lonesome Lady: A Hiroshima POW Returns (Translated to Japanese by Shigeaki Mori, Pub. by NHK Pub.). The spot where Cartwright landed was a vacant lot in a remote pine tree forest. He hid his parachute and threw away the bullets of a .45 caliber pistol. Fifteen minutes later, he met a peasant. It was Mr. Seiichi Tamai. Cartwright wanted to ask Mr. Tamai to take him to a Japanese military unit. However, Mr. Tamai was stricken by fear at the sight of this white man, who had a pistol in his hand, even though the bullets had been unloaded, and who was speaking in a strange language. Cartwright could see that he was afraid. He tried to make him understand his intention by gesticulating with body and hands. Eventually, Mr. Tamai started walking back along the path he had come. Cartwright followed him. He was taken to a the local police box (a very small police station). A little later, Looper also arrived at this police box. His feet were injured, looking awful. The police box was surrounded by people. Cartwright described the scene as follows:

Some of the villagers were excited, and when I reached for the pistol in order to surrender it, there was a big stir among them. The weaponry they had were just sticks and bamboo spears, which they had in their hands. At the door, a man with a hoe was standing perhaps to prevent us from fleeing. I put the pistol on the table and sat down beside Looper.

The policeman ordered them to empty their pockets. Cartwright, who was thirsty, appealed again through gesticulating and managed to receive some water. The two were blindfolded, hands tied behind their backs, and were taken elsewhere. A fair number of villagers followed them. At a place like a village plaza, their blindfolds were removed and they were made to sit down on the ground and spent a night there.

“People who surrounded us at a distance harassed us, through such deeds as beating or a twisting pinch; it was mostly women who did so as I remember.”

He writes that such beatings and pinching by women were common experiences of the American soldiers, who were captured as POWs at different places.

The next morning, an officer and several soldiers arrived in a small military truck. The POWs were again blindfolded, hands tied behind their back, and put on the truck. Then they were put aboard a train and transported for half a day. It was noisy where they arrived within what seemed to be the streets of a big city. Only later did Cartwright learn that it was Hiroshima. The two were taken straight to the Chugoku Military Police Headquarters. There they were unbound, released from the bindings that tied their hands, and were held in a big room on the ground floor, where five of the Lonesome Lady crew, all except Able and Pedersen, had already been accommodated. Cartwright felt relieved seeing their faces. Baumgartner of the Taloa and several other POWs had also been gathered there. The floor of the room was wooden. The POWs were told to sit down against the wall with their legs folded. They were strictly punished if they stood up or moved. They were prohibited from talking or sending signs by gesticulation. During the night, they were allowed to sit with their legs stretched forward. The room lights were always on, and guards held watch.

A bucket was set in the room as a substitute toilet. Cartwright and everyone held there must have been wondering: “What’s going to happen to me?” The day after his arrival, Cartwright was interrogated by an officer in an upstairs room. The officer spoke English very well. Tall buildings were visible through a window. In fact, probably because of the water he had in the village, Cartwright developed diarrhea. Every time the necessity occurred, he asked for an interruption of the interrogation, was blindfolded and was taken to the toilet. When he entered the small room, his blindfold was removed, and for a short time, he could glimpse a little river and a small bridge across it through a window beyond the door. The officer whose spoke English well started the interrogation in a friendly atmosphere. He sometimes offered cigarettes. However, as time passed by, his irritation became obvious. Sometimes during the interrogation, he hit Cartwright with something like a whip on the hands, arms and head. What the officer wanted to know about was the operations of the US military. To be more precise, he wanted an answer to why a big city such as Hiroshima had never been raided from the air. He never used the place name “Hiroshima” in his interrogation, of course. Cartwright told a fair part of what he knew. However, he had little knowledge himself why they assaulted departing from Okinawa, or what the situation was like regarding the accumulation of goods in the US military. Therefore, he had no way to answer those questions.

At that time, it was possible for Cartwright to presume the number of the US POWs had been increasing. The detention room became too tightly crowded. It seemed some newcomers were being held. He could vaguely feel that they had difficulty in settling the issue of how to accommodate the POWs. Then it was decided that Cartwright and several others were to be sent somewhere else.

Lieutenant Cartwright’s Doubt and Distress

Later in my life, I looked for and found Lt. Cartwright, who lived in the USA, and started exchanging letters with him. I had difficulty finding out where the 1st. Lt. Cartwright, pilot of the Lonesome Lady, lived. I decided to adopt the same method of search that I used domestically in Japan. It was the standard method of calling the telephone directory operators, telling them the name of the person, which is quite costly in case of foreign inquiries. His full name was Thomas C. Cartwright. With concern about the cost in my mind, consulting a map of America, I began a random search. Starting with Seattle in Washington State, moving downwards in the list, I made telephone calls. It was not my sole commitment, and I was not involved just in this matter, but sometimes I was hit by an overwhelming feeling of tiredness and desperation. After three years since this task started, Dr. Paul Satoh in the US contacted me, to inform me that, from a totally different channel, he found the address and telephone number of Dr. Cartwright. I acted immediately. I sent Dr. Cartwright the results of the research I had done. He sent a letter of thanks to me, along with his personal memoir. Through the exchange between Dr. Cartwright and me, the content of this memoir increased with new facts added, and finally it was published as a book. (It is titled A Date with The Lonesome Lady: A Hiroshima POW Returns.)

Cartwright correspondence to the War Department in search of the fate of his men.

In his letters to me he said that after the war he was concerned about those buddies who did not survive. What were their fates in Hiroshima? So many times he had contacted the military authorities and Defense Department. However long he waited, there were no responses. Two issues tormented him for a long time. One was, of course, that his men could have been killed in the atomic bombing. The second was about 2nd Lt. Pedersen, who had bailed out before Lt. Cartwright. What had become of him? After the war, the U.S. military announced that 2nd Lt. Pedersen died in the plane. This announcement was quoted in Enola Gay which was co-authored by Gordon Thomas and Max Morgan Witts, and 40 million copies were published all over the world. Naturally, the account was being acknowledged as “fact”. If it had been true that 2nd. Lt. Pedersen died in the plane crash, then it would seem that the pilot and officer in command, 1st Lt. Cartwright, bailed out earlier than his crew, because his own life was his highest priority. Cartwright had claimed all through the period after the war that he had confirmed there was none of the crew left in the plane when he jumped. He could not concur with the announcement of the US military. Captain Cartwright had been wondering about the fate of 2nd Lt. Pedersen. Until he visited Japan after the war, he thought Pedersen might have been killed on the ground, not in in the plane. However, I could at last verify the facts and let Cartwright know what actually happened, which wiped out this doubt and distress.

In the fall of 1947, two years after the war ended, coal mining was flourishing in Kyushu. There was an enormous need for wood to prevent the caving in of the levels and shafts in the mines. In order to purchase the necessary wood, many dealers from Kyushu came to Yamaguchi Prefecture. The Ikachi Village, Kuga County, was visited by numerous Kyushuites. The village decided to sell some wood produced in the village forest so that they would be able to build a junior high school. Around the top of the mountain forest of the village, a woodcutter who entered the forest heard a story from Mr. Ryuji Morishita who was engaged in agriculture. Mr. Morishita said he had seen remains of a human being in that area. The woodcutter immediately reported it to the police.

Then Police Station Chief, Tometa Matano explained the situation in detail to Phillip Tuless of the Investigation Dpt, Legal Affairs Division, the Supreme Headquarters of the Allied Forces. (GHQ Legal Affairs Division Document, No. 85. GHQ Materials are preserved in the National Diet Library Japan, Materials of the Constitution and Politics, as GHQ-SCAP materials.)

Let me quote the document.

High Public Security No. 1195

October 8, 1947

Police Captain, Tometa Matano, Takamori Police Station Chief,

To: Mr. Phillip Tules

Investigation Section of the Legal Affairs Division

Supreme Headquarters of the Allied Forces

Regarding: the discovery of the remains of a U.S. aircraft crew member, and the measure and action taken about this matter

The circumstances of the matter are as follows, which I report.

I. Around 9:00 a.m. of September 29, 1947, Mr. Fusaichi Kawamura, a laborer who is engaged in cutting mine timber (whose address: Koyagatani, Aza Shiwari, Shimo-Sou, Kuga county, Yamaguchi Prefecture), reported to Takamori Police Station as follows: A skeleton of a person who seems to be a U.S. (military) aircraft crew member lies in the mountain forest of Aza Hiraki-Koyagatani, Takamori-cho, Kuga County, Yamaguchi Prefecture. Uemoto Muneaki, Chief Inspector of the Legal Section, and five policemen went over, with Mr. Kawamura, Chikao Makibayashi, M.D. (whose address is: Honmachi-shita, Kuga-machi, Kuga County) and executed a careful inspection of the scene. (See attached report [1].) We found an identification tag at the scene (see the illustration [2]), which indicated the skeleton to be that of Roy Pedersen, a crew member of a US Consolidated B-24. Consequently, Takamori Police Station reported the matter to Yamaguchi Military System Headquarters and contacted the Iwakuni Commonwealth Military Police.

II. On October 1, 1st Lt. Robert L. Swanson and two others of 24th Unit, 52 Regiment of US Fukuoka Infantry arrived, and Legal Section Chief Inspector Uemoto and two others guided them to the scene around 11:30 a.m. On this occasion, 1st Lt. Swanson took the following four items that were found at the scene: the identification tag, a signal mirror, twenty pistol bullets, and a pencil.

III. On October 3, Masao Fukuda, a policeman stationed at the Kuma-cho Police Box, guided Lt. Col. Slan, M.D., and two others of the Iwakuni Commonwealth Air force, around 11:00a.m. On this occasion, Lt. Col. Slan took all the items except for the skeleton, which remained at the scene.

IV. Articles for Reference.

A. Since the careful look at the skeleton around 10:30 a.m. on September 29 until the arrival of 1st Lt Swanson (around 11:00 a.m. on October 1), the Takamori Police Station posted policemen and members of the Fire Brigade of the Aioi Village, Kuga County in order to preserve the scene of the incident.

B. While the man who reported the matter was identified previously, the first discovery was made by Mr. Ryuji Morishita, a peasant, whose address is : Aza Shiwari, Oaza Shimo Aioi, Aioi Village, Kuga County. Mr. Fusaichi Kawamura’s account follows: Around 13:00 p.m. on September 28, Mr. Morishita discovered a skeleton while he was inspecting the area for cutting trees for timber to provide structural support for mines; thereafter, Mr. Kawamura also went to the scene to confirm the presence of a skeleton. He reported that incident to Mr. Atsushi Suekane, a teacher of Aioi Village Junior High School, who persuaded Mr. Kawamura to report it to the police, which he did around 9:00 a.m. on September 29.

V. A sketch of the scene and report of the Medical Doctor who attended the inspection were created to document the findings.

VI. Separate attachments, (3), (4), and (5).

*It is clear that 1st Lt. Pedersen’s death occurred after he jumped from the plane. Captain Cartwright’s distress over the reports that his buddy died in the Lonesome Lady was unfounded.

The report by the Medical Doctor starts with the following prologue:

Around 10:30, September 29, I conducted a post mortem examination of the body for an hour, which had been discovered in the forest of Aza Hiraki-Koyagatani, Takamori-cho, with Mr. Uemoto, the Legal Section Inspector as the witness.

1. The body lacked clothes, flesh and organs and so on, leaving only the skeleton.

2. The body lay on its back, in the mountain forest, with the head to south, bottom to north, and face to east.

3. As the attached sketch shows, the bones were scattered, some of them missing, making it extremely difficult to record precisely; however, it was possible to see the bones which were presumed to be a broken shoulder blade, breastbones, spine, pelvis, upper arm bones, and thigh bones.

4. Each bone was much longer and bigger than those of ordinary Japanese, as shown in the attached sketch.

The details of the skeleton are described above. The cause of death is referred to as follows:

As explained above, extensive, complex fractures of bones accompanied by damaged blood vessels and internal organs caused the death of this person. It is also recognized that death occurred several hundred days ago. This concludes the post mortem examination.

September 29, 1947,

Medical Doctor, Chikao Makibayashi,

1006, Kuga-machi, Kuga County, Yamaguchi Prefecture

I let Dr. Cartwright know about this report.

Pedersen’s parachute failed to open. It might have been wet with seawater, or been caught on the hatch door or something else. The cause of the failure is unknown. It was certain that the only fatality due to bale out from the Lonesome Lady was that of Pedersen. I have no way to know if all the concerns Cartwright had were completely cleared. However, the doubt he had long held in his heart must have been resolved. Though, of course, even if he were released of the concerns and questions, which had long oppressed him as a heavy burden, the sorrow of the “deaths of his subordinates” would be difficult to be eased.

The Situation of the Taloa when it was shot down

The second of the two big planes that were shot down, the B-24 Taloa crashed in the mountainside of Yahata Village, Saeki County, Hiroshima Prefecture. The crew consisted of eleven members: Cap. Donald F. Marvin, the observer, 1st Lt. Joseph E. Dubinsky was the Pilot and the captain of the crew, 1st Lt. Rudolph C. Flanagin, the Copilot, Laurence A. Falls Jr., the Navigator, Robert C. Johnston, the Bombardier, Sgt. Walter Piskor, the Engineer, David A. Bushfield, the Radio Operator, Sgt. Charles R. Allison, the Top Gunner, Sgt. Camillous F. Kirkpatrick, the Nose Gunner, Sgt. Julius Molnar, the Tail Gunner, Sgt. Charles O. Baumgartner, the Lower Gunner. In contrast to the case of the Lonesome Lady, eight of the eleven crew members died in the plane, or immediately after it was shot down. Those who died inside the plane when it crashed are the following five: Capt. Marvin (Observer), Kirkpatrick (the Nose Gunner), Allison (Top Gunner), Bushfield (Radio Operator), Johnston (Bombardier), Falls (Navigator). The first to bail out of the Taloa were Sgt. Piskor, the engineer, and 1st Lt. Flanagin, the copilot.

Piskor landed on the rooftop of the factory of Mitsubishi Engineering, which was at Kwannon, the current West Airport. Surrounding the factory, a lot of Junior High School students, who were working there through gakuto douin (the Students Mobilization), were watching the parachuting US soldier. They stared nervously to see what would happen next. A scaffolding worker put up a ladder and climbed up to the roof. As seen from the ground, it looked as if the two men, one American and one Japanese, were wrestling each other, but actually the American was already dead, so the scaffolding worker threw the body down. The corpse was examined by Dr. Tanzo Kusakabe, Director of Mitsubishi Hospital, and was buried at the Kokuzenji Temple in Onaga-machi, Hiroshima City, (current Yamane-machi). In the beginning of December, 1945, the remains were disinterred by General Staff Masaharu Kikkawaa, an interpreter, and two officers of the US 8th Army, and were taken by the 8th Army.

Another US soldier, Flanagin, came down in the sea near the estuary of the Ota River, or Kusatsu. With the dye marker, the surface of the sea was colored so that the victim would easily be found. Flanagan was treading water. A fisherman rowed out in a boat, hit him severely with an oar, pulled him up into the boat, and took him back to the shore. He was more dead than alive, and eventually died. A medical doctor from the Mitsubishi Hospital was hurriedly sent. He tried desperately to revive Flanagan with artificial breathing, but did not succeed.

According to the report submitted by the director of Mitsubishi Hospital (a GHQ Material document), both Piskor and Flanagin had been seriously injured by the anti-aircraft shells, and the possibility of them dying was high, even if Flanagin had not been treated violently by the fisherman. His body was also buried at the Kokuzenji Temple in Hiroshima City and was later taken by the US military.

On the mountainside near where the Taloa fell, three US soldiers parachuted down: 2nd Lt. Dubinsky, Sgt. Molnar, and Sgt. Baumgartner.

Molnar was captured by the citizens who gathered around him at the spot where he landed, and he was taken to the military police. He was of small build for a U.S. soldier, so he did not frighten the Japanese people; to the contrary, he was nearly beaten by them more than once. An increasing number of people with bamboo spears, hoe, ax, or a sword surrounded him. Molner was shaking with fear. The military policeman or interpreter repeatedly tried to stop the violence by the Japanese. If they had not intervened, Molnar might have been killed by them. The fury of the citizens was that horrible. Molnar was eventually taken to a civilian’s house nearby, and after a simple interrogation, he was sent to the Chugoku Military Police Headquarters by truck.

Sgt. Baumgartner, who was also a crew member of the Taloa, bailed out around the same time as Molnar, and landed in the mountainside of Yawata, Saeki County, Hiroshima Prefecture. Either Baumgartner or Molnar was wearing a radio headset. He was repeating “Ohayo, ohayo”, speaking in his unfamiliar Japanese. When a Japanese soldier who was sent to capture him grabbed his arm, and asked him to follow him, he obediently did so. After a brief interrogation, Baumgartner also was sent to the Military Police Headquarters.

The interrogation of the two is recorded in the Hiroshima Atomic bomb Victims’ Journal. One of the two says, “I’m scared, I’m scared.” What is he afraid of? “Are you afraid because you are caught?” he responds, “No, not that.” He said, “In the near future, a bomb will be dropped, which will totally destroy Hiroshima. I know I’ll be killed, if I am here.”

Now, what was Dubinsky’s fate? He was last to bail out from the Taloa. The altitude might not have been high enough, as his parachute did not properly open, and before he crashed to the ground, the parachute caught on a pine tree, and he was hanging in the air. First, he seemed to be dead to the eyes of a lot of witnesses. In fact, the story about Dubinsky is an enigma.

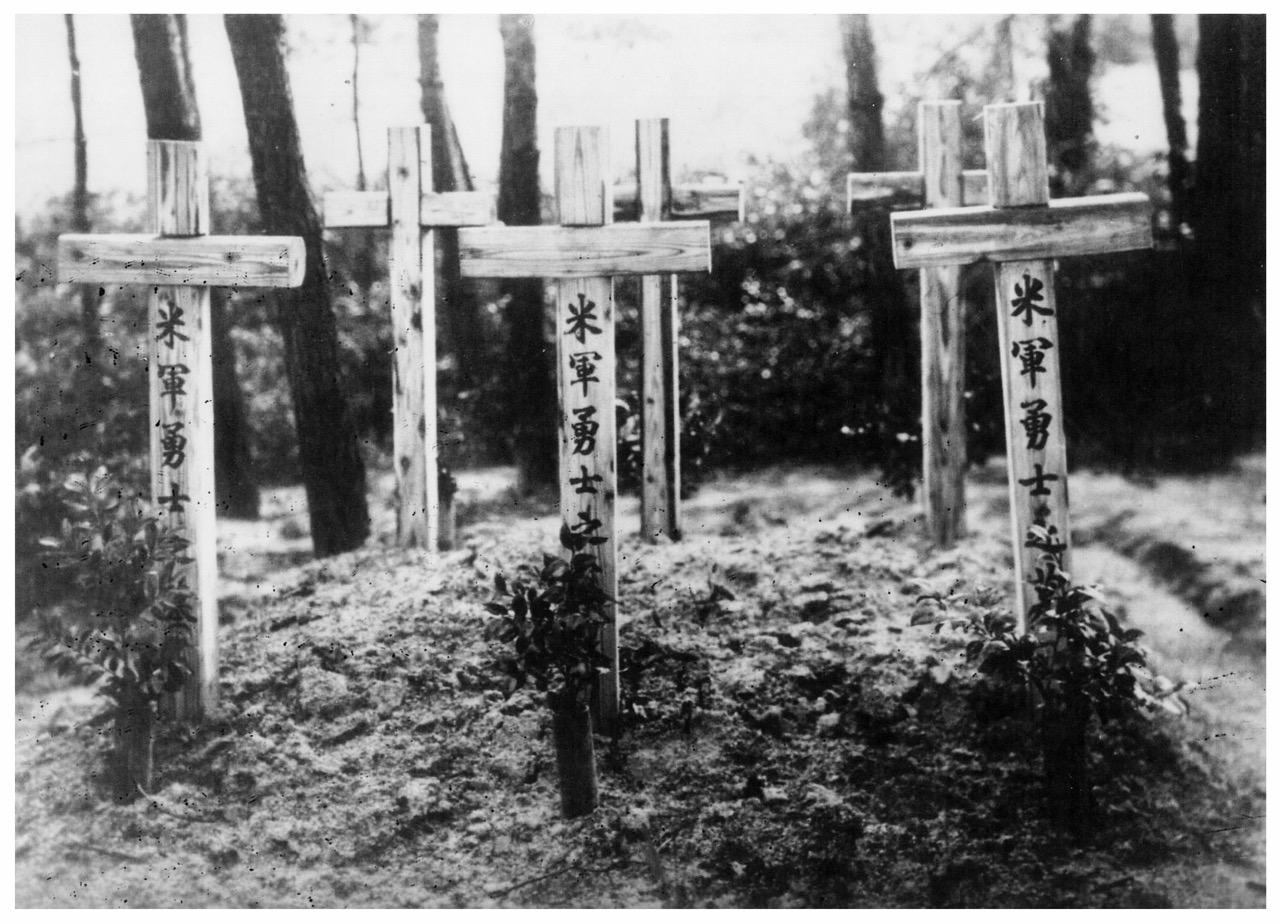

Graves of Taloa crew members.

The US soldiers who were inside the Taloa when it crashed were the remaining six: Cap. Marvin, S/Sgt. Kirkpatrick, Sgt. Allison, T/Sgt. Bushfield, 1st Lt. Johnston, and 1st Lt. Falls. After the war, six grave markers for them were put up near the scene of the fall. However, according to the GHQ materials, 2nd Lt. Dubinsky is recorded as killed at the scene of his fall, completely contrary to the view that he was captured alive. Had he died at the scene, seven men died in the Taloa crash. In other words, this account says that 2nd Lt. Dubinsky was dead when he was hanging in the air. I will eventually discuss the validity of these accounts.

The American POWs who bailed out of the bomber were all brought to the Headquarters of Chugoku Military Police, and were interrogated. The Foreign Affairs Section of the Headquarters was in charge of the POWs. They made records about each one of them; however, nearly all of the documents were destroyed by the fire caused by the atomic bomb.

On the 28 July, 1945, Porter and Brissette flew SB2C Helldiver #210, second from the bottom.

The Cruel Fate of A Young Aviator (I)

Now the account moves to what happened to the twenty small planes. While the bombers departed from the airport in Okinawa, all the small planes departed from the aircraft carriers. On July 28, 1945, Raymond Porter and Normand Brissette climbed into the SB2C Hell Diver designed for two, and departed from the USS Ticonderoga. Their target that day was the battleship Tone. The Tone had been a veteran strong ship, seeing action all through the Sea Battle of Midway to Leyte. Porter was the pilot and Brissette was the wireless (radio) operator and gunner. They were aboard the SB2C Helldiver, waiting for the “go” sign. Around them, other planes such as the F6F Hellcats and the TBM Avengers were similarly waiting for “go”, their wings spread in line. At 7:45, the thirty-nine first starters departed with a roaring sound. Eventually they formed in formation and slowly approached the Tone, which was anchored along the coast of Etajima Island. As they came closer to the target the anti-aircraft fire from the ground became fiercer. They increased the speed and advanced further. They lowered the altitude from 15,000 feet to 3,500 feet, and all thirty-nine of them started to drop the 260 pound-bombs held in the wings, and 1,000-pound-bombs, which were kept hidden in their bodies. The Tone received a devastating blow. It seemed that the SB2C Helldiver in which Porter and Brissette flew could make it safely to the USS Ticonderoga. Actually, after the war, a quite detailed account was written about 1st Lt. Porter. Mr. Goodspeed, a staff member of the Naval Museum in Pensacola, Florida, wrote a feature story about him and quoted letters to his parents in his article titled “The Way to Hiroshima: a Naval Navigator Pursued”. I acquired this article, through which I learned about quite an ordinary life of a young soldier, and the cruel fate he met. This is precious material to know about the personal footsteps of a military man, crossing the Pacific towards the west, and further westward, until he meets the atomic bombing. Although I did similar research on the other US servicemen, for various reasons my attempts were not successful. Guided by the article by Mr. Goodspeed, I followed the experiences of this young aviator, Porter.

Porter was born on April 22, 1921, in Butler, Pennsylvania, a small country town. In the 1939 Yearbook of Butler High School, he is described as “quiet and charming”. His future dream was to become a certified accountant and earn twenty dollars a day. The Great Depression of 1920 must have greatly affected his generation. His dream and goal was consequently very specific. However, dreams often diverge from reality. In the fall of 1939, as his first job, he was employed by a grocery store. Two years later, the aircraft of the Japanese Navy air-raided the US Pacific Fleet in Pearl Harbor, destroying a brief time of peace. The start of WWII changed the lives of many people. Raymond Porter, as with many of his generation, had a patriotic streak in his heart, and decided to register in the US Navy. Perhaps excited by the Battle of Midway and the thought of flying, he chose the course of the Naval Aviation School. Until the spring of 1945, he was enrolled in the Preliminary Naval School of Iowa State, one of the states where many educational facilities of the USA are centered. The training at the preliminary school, which was designated to educate civilians into the way of military units, seems to have strongly impressed the new cadets. Porter’s letters are quoted in the article. This is what he wrote to his family soon after his arrival in Iowa:

“Oh, we always have to act very quickly here and do everything in that way. The instant I wake up in the morning, I feel like I’m dying, and when I get in bed I feel dumb because I’m not dying.” Similar days and weeks had passed after that, and life went on observing tight daily schedules, keeping to monotonous rules. Such events as 15-mile hikes or obstacle course races made Porter and others feel disgusted. Moreover, inspection of necessities and rooms, also exams on every Friday lay hard on the young men. “An awful number of them usually flunk in the last weeks,” says Porter. However, Porter prevailed. He received his first flying training at NAS Lambert Field in Missouri State. He got aboard the famous Yellow Peril, and experienced 104.5 flight hours. Enduring the sultry heat in the classroom, he learned about the engine of the airplane, indicators, Morse code, and so on. He also knew there were many different types of Naval flyers. In a letter around this period, he writes, “We cannot say it is enough for the Navy if they have only one pilot. Twenty months had passed since the US broke into war. One year before, Porter was just a young man, who lived an ordinary life. “Last year, we, four pairs of us, went out to Lake Connuatt. Now one of them is dead, and two others are abroad.” When the summer was gone, and fall had come, his basic trainings were finished. In September 1943, in order to receive advanced training, he took a train to Pensacola.

The Cruel Fate of A Young Aviator (II)

After he moved to the newly opened NAS Whiting Field near Milton, Florida, nothing good happened for Porter. “The way of life here was so old-fashioned and conservative that people never gave even a cup of hot tea to newcomers.” “What a damn place it is. Scenery where there is nothing but sand and trees is spread for a hundred miles.” A short trip to Pensacola, which he made soon after arriving, left him with no memories. Reminiscence of his homeland, Pennsylvania, became deeper and deeper. “The narrow streets and pedestrians’ path. In the width of one third of the main street of Patular are are around ten times as many people. Buildings are old and nearly collapsing. I have never seen such a great number of soldiers in such a narrow space. The more I’ve seen of the South, the more I love the North.” Porter was receiving training both in flying and on the ground. The class work was especially strict, and he complained in his letter. “Regarding the ground training, there is a lot I have to scream about. It must be the same for everybody.” It was the days of improved single-engine planes. His everyday life was spent on learning how to use the flight machinery and tools, flying, including acrobatics. “I get up and eat in the morning, fly once, twice or three times a day, eat again and go to bed.” That was Porter’s typical day. “Nothing more.” In December 1943, he could not get the duty assignment he had expected. In addition, on Christmas Eve, a buddy among his cadet group died, so it did not turn out to be happy holidays. “I looked at the operations plan, saw that I am assigned to dive bombing, and I was quite disappointed. But, I believe I have to do the mission I’m given. It might be possible to change the my assignment, but I suppose not.”

In February the following year, he was commissioned as an officer. Even though he might have had some dissatisfaction, his spirits were high in its own way. He spoke as follows, when he climbed up the stage to receive his Navy commission. “Once or twice, I felt my knees wobble.” That night, he danced with girls till dawn. It was the last days for Porter at the Navy Air Force Preparatory School. He finished SBD Dauntless Dive Bomber training at NAS Daytona, also in Florida, and was certified for aircraft carrier takeoffs and landings at Lake Michigan. Porter, who had just been promoted to Naval 2nd Lt, viewed the fleet assembled at the port and wondered to which aircraft carrier he would be assigned. The selection of the crew for the fleet started in July 1944.

It was just before this that news of the Normandy Landing Operation appeared. As is known, nearly 3 million men of the Allied Forces were standing by, among which around 200,000 crossed the Dover Strait and landed in Normandy of France. It was the Greatest Historical Landing Operation, indeed. The news made young people like Porter excited, by all means. The so-called D-day was on June 6. Three days later, he wrote in a letter: “I thought about the fact that a lot of my buddies, who I know so well, are overseas.” “It seems they are doing so well. I hope they will keep doing well. Perhaps the war might end earlier than I had expected.” After that, Porter himself was put in such a state, that “I now have few relaxing days.” The admiral of the carrier to which Porter was assigned was Lt. Col. Maxell. He was an experienced officer who had been actively involved in Guadalcanal. Under his command, the pilots and crew of the 87th Squadron concentrated on mastering the complex mechanics of the SB2C Helldiver. During the month of August, Porter added more than 136 hours of flight time aboard the SB2C, being trained as the pilot for the dive-bomber. Towards the end of August, a chance came for him to shift to be a crew member of a fighter plane, which he had long wanted. There had been an order to the 87th Squadron to reduce the number of the crewmembers of the SB2C from thirty-six to twenty-four. After a difficult choice to make, Porter decided, after all, to remain in the 87th Squadron as the crew of the SB2C. He did not want to waste the specialized training he completed. No one knows if this choice was right, and there is no way of knowing that. By September of 1944, the members of 87th Squadron were to move to southern Virginia. The training here went on for two months, which included the simulation exercises of attacking military facilities along the coast line, off-coast navigation, and transportation campaigns. They were never safe training missions. Although they did not have major accidents, he writes in his letters that they had two incidents which could have been disastrous, had anything gone wrong. In late November, the aircraft carrier Randolph finished its check-out cruise, and was proceeding to the Caribbean Sea on the 21st. There, training was conducted for a month, and then the ship went through the Panama Canal, bypassing South America on the way to the west coast of the United States.

On December 31, 1944, the Randolph arrived in San Francisco and anchored at Hunters Point. On the deck, the persistent scars created by two kamikazes were vivid reminders of the possible danger the ship would meet in the future. In January of the next year, the aircraft carrier Randolph departed to the Pacific Ocean. However, the 87th Squadron had to join up with the 12th Squadron, and change course to Hawaii in order to take on a new mission. The crew boarded the Bunker Hill on January 24. At that time, Porter writes his last letter to his parents. “This is secret information, but by the time you receive this letter, I would have already gone. The preliminary trainings have finished, and a big game is going to start. Everything will go all right, so please do not worry. I should be able to take care of myself. And I will come home safely.” On January 28, the 87th Squadron arrived at Pearl Harbor. After some rest on Maui, they had to start preparations for a new battle. But, he writes this island was a very attractive place.

On May 11, the time arrived for those young pilots to join what Porter calls “a Big Game”. The 87th Squadron boarded the carrier Ticonderoga, and advanced toward the Western Pacific Ocean and the battlefield. On May 17, after attacking an airfield on Tarawa to the south west of Hawaii, where a fierce battle was once fought, the carrier Ticonderoga joined the Task Force unit were it took command of naval support for the land battles in Okinawa. After one month of being on this duty, they were re-assigned to the Philippines. In the Philippines, the engines were repaired, and then they prepared for attacks within the Seto Inland Sea of Japan, departing from Guam.

This time they were to advance through the sky over the enemy country. It was expected that a lot of damage would befall them. On July 24, among the thirteen planes that departed the Ticonderoga to attack the Battleship Hyuga, just five returned to the carrier. The other planes were either shot down or made emergency landings in the sea because they ran out of fuel. The admiral of the ship was shocked. Of course, all the crew was shocked. In short, that revealed they had underestimated the Japanese Forces.

Four days later, on the 28th, the assault on the cruiser Tone, which was moored in Kure, was carried out. As with the Hyuga, the counterattack from land was expected, so it was decided to shorten the intervals of the departures of the SB2C Helldivers. On this occasion, Raymond Porter climbed aboard with Normand Roland Brissette. Five months before this departure, Porter wrote as follows, as a comment to a friend who was killed in action: “When this war ends and I go home I wonder how I shall feel about not being able to meet again with those who were once my friends. It is wrong that so many young men shorten their lives in this way. But this is how it is with war. What we can do is to hope and pray for the early end to this war.”

On July 28, after attacking the Tone, the aircraft piloted by Lt. H. Paul Brehm, flying behind, noticed that Porter’s aircraft was spewing smoke. It was hit by anti-aircraft fire from the Tone. Porter’s plane moved away from the formation, trying to make an emergency landing. The emergency landing spot was the sea off Ohshima County, Yamaguchi Prefecture.

They flew from above Etajima Island, descending, emitting white smoke, to Yamaguchi Prefecture and ditched in the water. Seeing that, another plane dropped a rubber life-raft and the crew witnessed both Porter and Brissette swim up to and into the raft. The two waited for rescue. Just a little before the relief squad from the PMB Mariner arrived they were found by a landing boat of six cadets of the Japanese Akatsuki Unit, and were captured as POWs. Porter and Brissette were sent to the Chugoku Military Police Headquarters in Hiroshima via the Military Police Ujina Branch.

The Shooting Down of Small US Planes

A Curtiss SB2C Helldiver, the same model as the one flown by Raymond Porter and Normand Roland Brissette, who made an emergency landing on the sea being hit by the anti-aircraft fire while attacking the Heavy Cruiser Tone.

A TBM Avenger torpedo bomber, the same model as the one flown by Brown and Lockett, hit by anti-aircraft fire of the Haruna and fell into the sea around 3 p.m., 28 July.

Another small plane, a TBM Avenger (from squadron VB-86) that departed from the US carrier Wasp, was hit while it was attacking the Haruna. Anti-aircraft fire from the Haruna shot the plane down and it fell into the sea off Ninoshima Island around 3:00p.m. July 28. The crew, pilot, Lt.(jg) Joseph Donald Brown, and the radio operator and bomber, Sgt. Frederick Charles Lockett, were floating on the sea off Ninoshima, and were found and rescued by a boat that was crewed by five personnel of Sachiura Detachment of the Vessels Practice Department. The men were captured and were then POWs. They were sent to the Chugoku Military Police Headquarters via the Military Police Kure Branch.

Grumman F6F Hellcats, the same model as the one flown by John Joseph Hantschel, hit through the fuel tank and made an emergency landing on the sea.

The last one captured, 2nd Lt. John Joseph Hantschel, was on board a Grumman F6F-5 that departed from the US Aircraft Carrier Randolph. Off-shore from Kumage County, Yamaguchi Prefecture, the fuel tank of his plane was struck by anti-aircraft fire. Due to the loss of the fuel, he made an emergency landing in the sea. (Another view says it was because of engine damage.) While he was floating westward in a one-man life- raft, on July 29, he was discovered by a fisherman Shinakichi Morishige, off Kiwa Village, Yoshiki County, Yamaguchi Prefecture. While fishing, he saw an American soldier in a life-raft waving his hand for help. The fisherman had a lot of nerve and dared to row up to the raft and rescued him. The soldier was wearing a jump-suit. This soldier Hantschel was sent to Yamaguchi Military Police via local police, and three military policeman took him to Hiroshima: namely. 2nd Lt. Yukio Aoyama, Sgt. Daisaku Tanaka, and Pt.1st Jukichi Kakimoto.

All the above mentioned information is based on the “Report on the Guards of the US Aircraft Personnel and Other Matters”, issued by the Dept. of General Affairs, Chugoku Administration Bureau of Demobilization, former Chugoku Army Headquarters.

Of the twenty-two large and small airplanes, the crew members of seventeen planes were not rescued by either side. Either the plane sank into the Seto Inland Sea or crashed into the mountain side of an island. It seems that most of them were killed in action, although just a few were rescued. (The author confirmed, through the GHQ materials, twenty-one deaths and the survival of three.) In short, regarding the US aircraft, some crew members from five planes survived and became POWs: the Taloa, the Lonesome Lady, the SB2C Helldiver, the TBM Avenger, and the F6F Grumman. Eleven members were aboard the Taloa, and eight of them died during or immediately after the crash. Nine were aboard the Lonesome Lady, and only one of them fell to his death. Among the crew of the SB2C Helldiver (two were aboard), the TBM Avenger torpedo bomber (two were aboard), and the Grumman F6F (one was aboard), no one died; all five survived.

It means, after the five plane crashes, the number of those who became POWs were eight from the Lonesome Lady, two from the Taloa (not including Dubinsky), two from the SB2C Helldivers, two from the TBM Avengers, and one from the Grumman F6F; a total of fifteen personnel from five planes. I will write about Dubinsky of the Taloa later.

Among the fifteen, fourteen of them (not Able of the Lonesome Lady) were brought to the Chugoku Military Police Headquarters of Hiroshima. It was then that the presence of the US POWs in Hiroshima became reality––but this was never supposed to happen.

[1] In A Date with the Lonesome Lady, p 27, Cartwright states that Neal was with the others at the rear hatch.

[2]Loc. Cit., Cartwright stated that Bill Abel told him that he heard the bail-out bell and he opened the rear hatch.

[3] Ofuna was the only Navy-operated POW camp.

At the Bomber Crash Sites

...At the Scene Where the Taloa was Shot Down

Mr. Kiyoshi Suzutani captured one of the American soldiers who parachuted down from the Taloa at Yawata Village, Saeki County,..