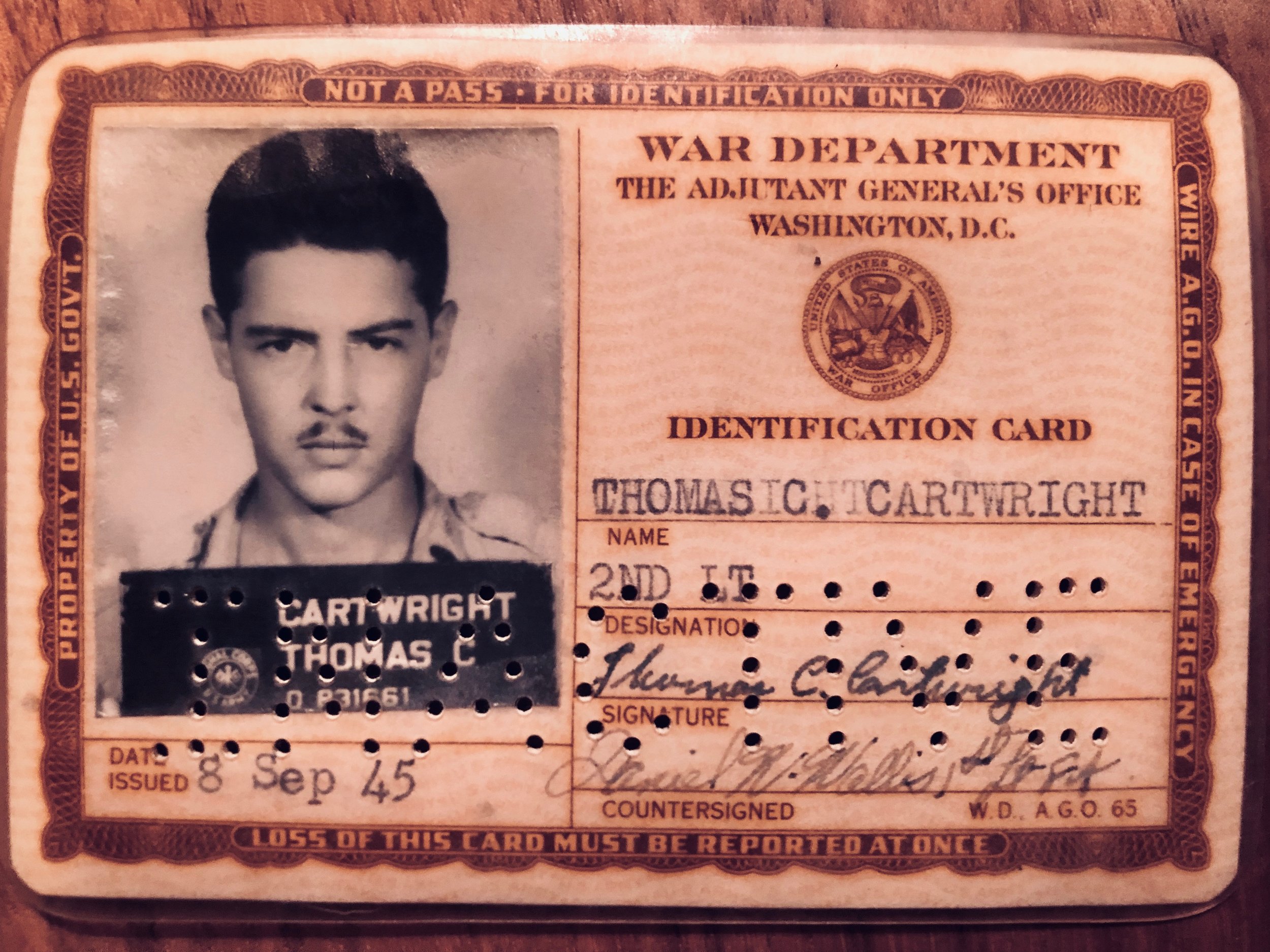

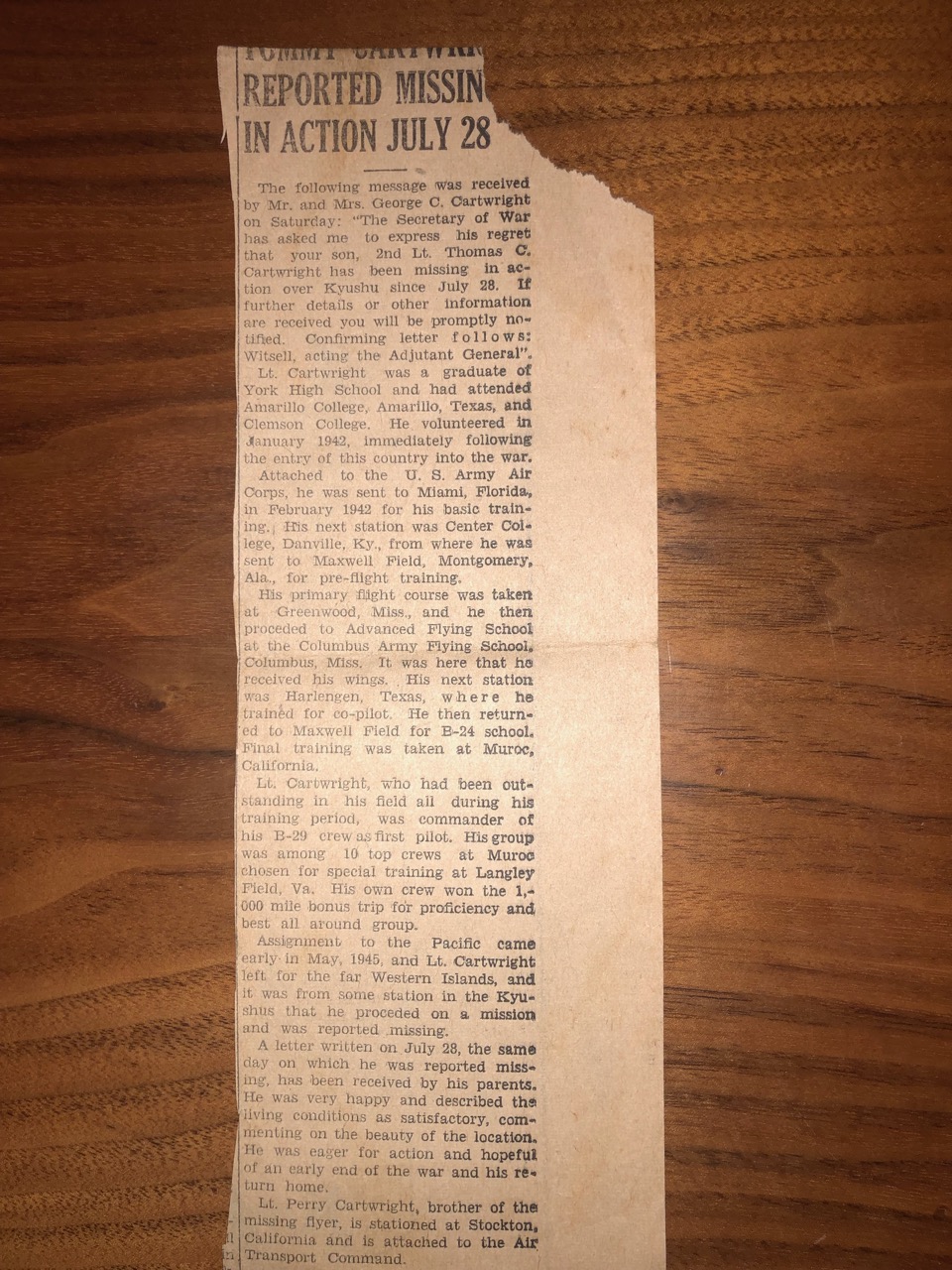

Known by his older family and some of his crew as Tommy, and by others as Tom, Dr. Thomas C. Cartwright and his crew, along with Shigeaki Mori, were the principal inspiration for this documentary website. Cartwright's crew were extensively accomplished in flight, radar, and bombing training. They flew the first B-24 combat mission from Okinawa to China, then followed orders to fly just one other combat mission---the Haruna mission. This website chronicles the climax of his wartime service, particularly from July to September, 1945. He is most widely known for his distinguished career in animal sciences at Texas A&M University.

Cartwright was promoted to 1st Lieutenant then honorably discharged just after the war. He returned to York, S. Carolina matured through military training and dangerous combat and POW experiences. As a POW in Omori Camp near Shinagawa, Yokohama, and Tokyo, Tom vowed to marry his one true love, Carolyn (nee Hobson) (please contact site editor MS using the mail link below for access to the private pages) and return to a peaceful life "as a farmer"; he succeeded in earning the lifetime devotion of one of the most lovable, supportive, devoted, and happy persons he could ever hope to find. In Texas, Tom and Carolyn raised their own clan before retiring to be near their children and their families in Utah. They and "their allies" represent what families and friends are meant to be, and are themselves a national treasure.

Tom and Carolyn had close, life-long friends who served in WWII, like Luther Bird (wife Bernice), who served in the WWII European theater and ended the war as a POW. Yet many other career-long colleagues had no knowledge of Dr. Cartwright's experience as a pilot and POW in Japan. Notable even amongst other stoic veterans, he rarely ever spoke of his historic war experiences but was very forthcoming when interviewed by news media whom he respected. With his seminal work in animal husbandry and genetics, and a book on ecological approach to livestock production, Dr. Cartwright was dedicated to a peaceful life, helping to feed the world.

Tom Cartwright leaves a legacy of love to his family and friends. He earned respect and admiration from his colleagues, fellow faculty, and students for reasons that are so rich and varied that they depend upon who you ask. Tom and Carolyn were, in every sense of personal character, role models to everyone who knew them well. In contrast, it is unfortunate that many of the Pacific War POWs never fully recovered from the deprivations, humiliations and indignities of their extended and severe war experiences.

Prisoner of War

28 July – 29 August, 1945

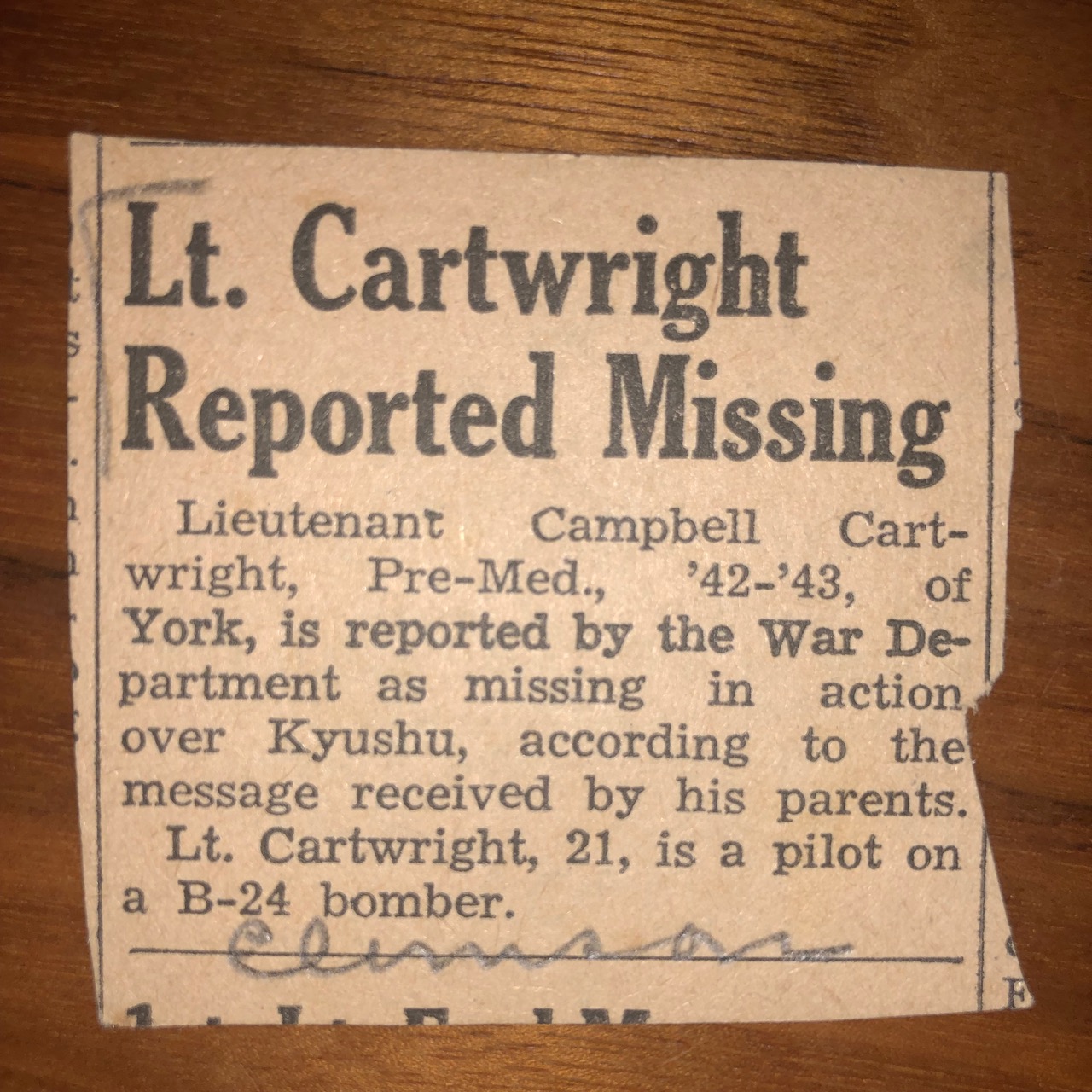

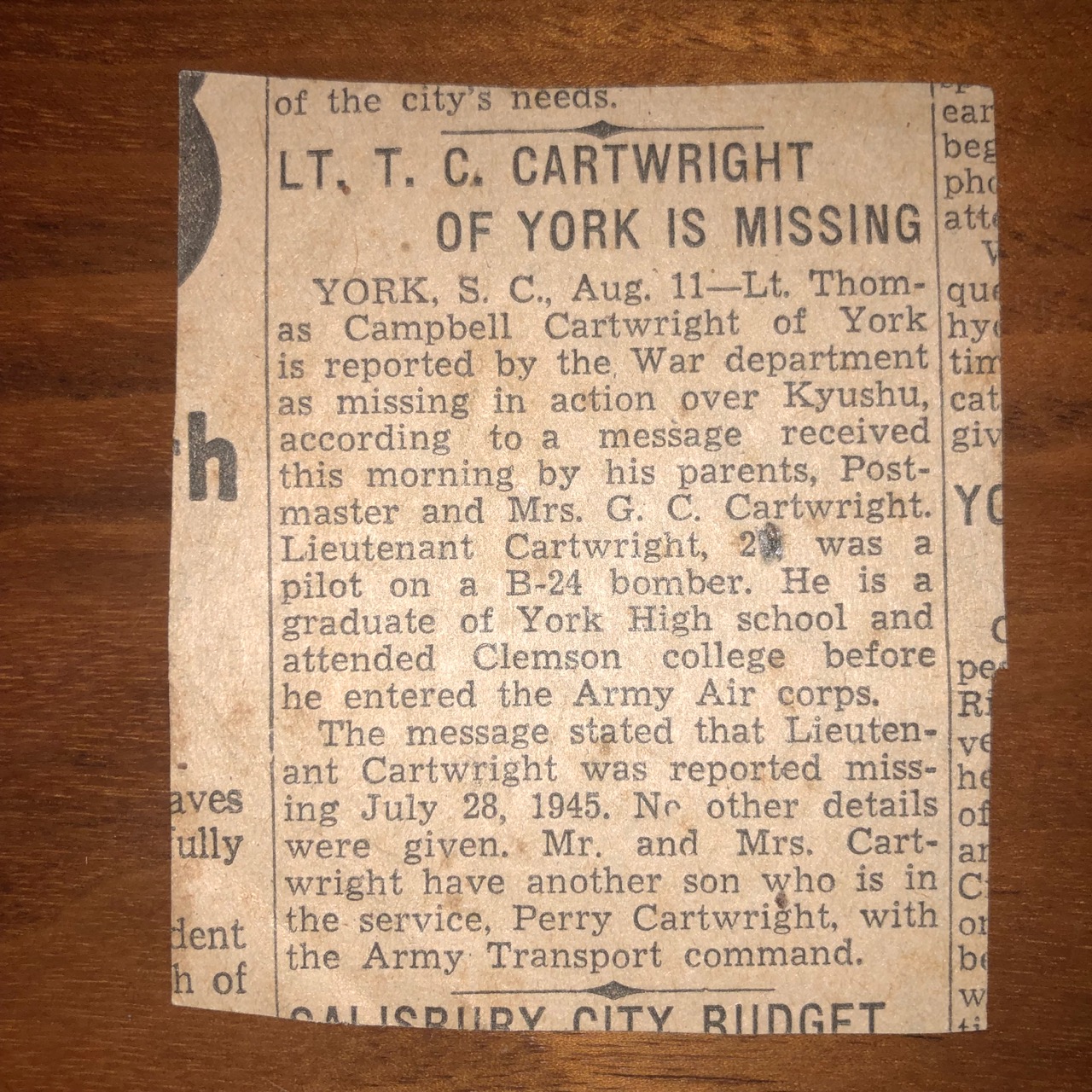

After parachuting into a clearing near Ikachi, Yamaguchi Prefecture, and discarding the ammunition from his .45 pistol and following at the local farmer Seiichi Tamai to Ikachi, Cartwright was marched to Yanai, then taken to Hiroshima by truck and train. There he joined six of his seven surviving crew men at the Kempeitai Chugoku Military Police Headquarters. on 31 July, 1945, he was transferred by train to the Imperial General Headquarters in Tokyo via Osaka. It was fortunate for him that he, Navy airmen Donald Brown and Frederick Lockett quickly left Osaka as their guards protected them from at least one angry mob. Within a few weeks, more than 50 American airmen POWs in Osaka were executed just after the Emperor spoke publicly for the first time to announce surrender. Cartwright’s parents learned about 10 days after his capture, just a few days before the war ended, that he was missing in action.

After hearing the Japanese Emperor’s speech and surviving his own mock or aborted execution, Cartwright was taken by coal-burning truck through the bombed out streets of Tokyo to a dredged up island in Tokyo Bay off Yokohama, the prison camp known as Omori.

In photographs and a letter to his wife, US Navy Photographer John Swope chronicles the moment of Cartwright's liberation from Omori:

“We rounded a turn in the channel and were immediately besieged by a hundred clasping hands and arms. They continued to cheer and yell and shake our hands and clap us on the back and fall on us in tear-soaked embraces...After the first initial pictures I took from our boat of the PWs cheering and waving with the American, British, and Dutch flag on high, I wasn’t able to take any for another ten minutes...I know it can never show what we saw and felt.”

Smiling Lonesome Lady Pilot Thomas Cartwright is third from the right (wearing an unbuttoned shirt) in this image of Prisoners of War who were rescued from the Omori Camp in Tokyo Bay. This was the first landing of American Marines on the Japanese mainland, ordered by US Naval Comodore R.W. Simpson, and Commander Harold Stassen, reportedly sanctioned by Admiral William Halsey, but illegal, since since no peace agreement had been signed by the warring countries. Cartwright was to be the only USAAF Hiroshima POW to survive the war. Two other Hiroshima POWs, Naval aviators, also were liberated from Omori. Crewmate Bill Abel was released soon after from the notorious Japanese Navy "detention camp", Ofuna. (Photo credit: Probably John Swope, USN, but possibly his non-commissioned assistant George P. Gates, Jr. Swope’s team also included cinematographer Robert Walton, who also filmed this scene.)

The Press Release caption for the photograph, above.

James D. Landrum carried the U.S. flag in these photos. The flags were carefully created by the POWs using bedsheets and colored pencils and were a tremendous symbol of pride for these men, some who were regaining their freedom after three years and eight months working at hard labor under deplorable conditions.

The War Ends

“How stupid the whole thing was. ”

The Cartwright family and community in York, S. Carolina learned of Tom’s survival and liberation the first week of September.

Courtesy of the Cartwright family.

The high speed transport Reeves was the first U.S. Naval vessel to drop anchor in Tokyo Bay before the formal surrender.

Just behind the mine sweepers and destroyers that entered Tokyo Bay on 28/ 29 August was the USS Benevolence (AH-13).

To the end of the War the air crews of Kelley's Kobras, the 494th Bombardment Group, lived up to their motto last shall be first. One of the last two B-24 Liberator "replacement" flight crews assigned to the last Bombardment Group of the 7th Army Air Force, shot down while trying to sink the last battleship of the Imperial Japanese Navy, the last of his 9-man crew to bailout, one of the last to be interred at Omori POW camp when the Japanese surrender was accepted, it was Tom Cartwright's great fortune to be amongst the first POWs rescued from internment in Japan. Admiral Halsey reportedly answered "they are our men, go get them" to Commander Stassen's request to immediately rescue the Allied POWs from Omori POW Camp, a dredge-created island near Tokyo and Yokohama. That was five days before the formal surrender on 2 September. Although he was a prisoner for just 32 days, he lost a pound of weight a day (at least the first several weeks), an astounding amount given his stature. Still, he was one of the healthier men so he was quite able to clamor into the first wave of riotous American, British, Australian, and Dutch POWs celebrating their liberation in the 29 August, 1945 photograph, above. His good health accorded him berth on one of the later landing craft, allowing the sick and injured from Omori and the nearby Shinagawa "hospital" groups to be evacuated first to the Benevolence or another hospital ship. Cartwright was the only one taken from Omori POW Camp to a Destroyer (perhaps Swope's Hawkins, or the Nicholas?), then transferred to the cruiser Reeves. There, he was in sight of the USS Missouri during the signing of the surrender on 2 September. He wrote that he did not know what was going on, but it was momentous given that 400 B-29's and 1500 carrier planes performed a flyover. He was able to send a telegram home from the USS Monitor (LSV-5). As with many POWs to follow him, Cartwright was transferred back to mainland Japan aboard a landing craft, and taken by U.S. Army 6x6 Army truck past waving crowds of Japanese to Atsugi Airfield, south of nearby Yokohama. There, he boarded a Douglas C-54 transport plane that returned him to the airfield where his last combat mission began, Yontan, Okinawa. After a dramatic welcome from his commanding officer, who was then writing to his father, George Cartwright, to notify him that his son was presumed killed in action, and the thrill of being reunited briefly with his tailgunner, Bill Abel, the men boarded ships to the Philippines. From there, Cartwright returned to the United States aboard the same hospital ship that entered Tokyo Bay so early on, the USS Benevolence.

“Late that evening I was one of the last to board a landing craft which headed out into the bay to berth alongside a beautiful white hospital ship - U.S.S. “Benevolence.” It’s name was more than upheld, for never was such kindness, gentleness and understanding, displayed as by the officers, nurses, doctors and men of that magnificent American vessel.”

Cartwright noted that in San Francisco, the men were met at the gangway by Fiske Hanley II "and other brass". Hanley had been a B-29 "special prisoner" who later wrote an overwhelming account of his solitary confinement in a dungeon and astonishing cruelty at the Kempeitai Headquarters in Tokyo, abutting the Emperor's palace (Accused American War Criminal, Eakin Press, 1997). Hanley was transported on 15 August, a day earlier than Cartwright, from his Special Prisoner dungeon in Tokyo to Omori via a coal-burning truck. He boarded the hospital ship Benevolence and was transferred to the USS Reeves, then traveled nearly the identical path as Cartwright from there to Atsugi on the mainland via Landing Ship Tank (LST) and from there to Yontan aboard a C-54. Hanley's written narrative is quite detailed. After his crafty liberation from hospitalization in an Army Field Hospital in Okinawa and surviving a disastrous Typhoon, Hanley returned to the United States via C-46 and C-54 aircraft. He hoped to greet and surprise the first POWs returning by ship, the Benevolence, including "friends from Camp Omori who had left me behind in Okinawa":

“...I had beaten them to the USA. I was on the dock when the ship tied up. Along the ship’s rail overhead, I spotted a few of my Kempei cellmates. As they came down the gangplank they were shocked to see me there waiting for them...”

Like Cartwright, Hanley was one of only two survivors of his bomber crew. Among his Kempei Tai cellmates, 62 men were killed by sword and fire during an air raid on 25-26 May, on Shibuya, Tokyo. Nearly 70 years later, in the year 2014, Cartwright discussed with one of the editors (M.S.) Laura Hildebrand's book Unbroken about Louis Zamperini's torture at Omori and elsewhere. Cartwright stated that the book "emphasized the negatives...but as you say, it [conditions and treatment of the POWs at Omori] was horrible". He also stated that if you wanted to read what the experience was like for captured B-29 (bomber) crews, the so-called Special Prisoners, read Fiske Hanley's book Accused American War Criminal.

Dr. Cartwright's informative letters to the War Department appear to have been unanswered. This letter was obtained by Barton Bernstein from a Freedom of Information Act request.

Recording the History

After returning home to South Carolina, Cartwright came to realize that the location where he had arrived blindfolded and held prisoner with six of his crew members and other servicemen, was Hiroshima. Cartwright made numerous efforts to learn from the U.S. government what happened to his crewmates. He reached out to the crew families to share what he knew and could surmise of their fates. Upon occasion, he chose to keep information private about injury, abuse, even torture of his crewmen. Tom was rarely outwardly sentimental, still, he thought of his crew as family.

He was very surprised to have the opportunity to know and develop friendships with Japanese citizens in Hiroshima. A substantial portion of his wartime memoirs were written about what he learned about the fate of his crew men through correspondence with these new friends and what he learned firsthand from accepting the invitation from Keiichi Muranaka and Shigeaki Mori to visit the locations in and near Hiroshima where he was shot at, crashed, imprisoned, and where his men were imprisoned and died. His interviews are the recorded history of his men, and they are a treasure.

In 1984, Robert Karl Manoff interviewed Cartwright and wrote an extensive account in the New York Times Magazine. In an interview by Harold Channer in 1987, Gary DeWalt describes details of his research efforts and findings along with Barton Bernstein, a Stanford expert on the Truman Administration who filed for information about the Hiroshima POWs under the then new Freedom of Information Act. DeWalt had access to opened government records, and he produced the first documentary video about the Hiroshima POWs, Genbaku Shi: Killed by the Atomic Bomb.

Genbaku-Shi - Killed by the Atomic Bomb - Video documentary researched and produced by Gary Weston DeWalt/Public Media Arts told the fate of members of American POWs, particularly the B-24 crews of the 494th Bombardment Groups 866th Bomber Squadron, Taloa and Lonesome Lady who were prisoners of war in Hiroshima. Most of these American servicemen were killed by the dropping of the Atomic Bomb on Hiroshima.

An audio transcript as well as a written transcript of an extended interview of Dr. Cartwright by Chris Simon on 27 May, 2004, is available from the Veterans History Project website and can be heard here:

Following the war, Tom Cartwright's seminal work in animal breeding/genetics and the many students he mentored hallmarked his "world class" career. He is most widely known for his work as a tenured professor at Texas A&M University. Following graduate school there, he stayed on as staff, faculty, until ultimately retiring to professor emeritus status, His academic career spanned 43 years––during which he did not call in for a single sick day. His tremendous work ethic was much admired and can scarcely be understood today. When once he was struck with a miserable case of shingles (an unfortunate legacy of his exposure to chicken pox), he soldiered on discreetly in his university office, behind a closed door, with his shirt removed and draped over his desk chair to relieve the insufferable itchiness. Throughout his life, Dr. Cartwright mentored and guided the lives of innumerable people––students, family, and friends worldwide. His family and friends would be pleased for him to be remembered for his entire lifetime as a dearly loved family man, friend, teacher, researcher, and for who he was beyond even that.

The authors of this site have weighty awareness of the potential impact new information may have on the families and friends of the POWs. In our chronicling of the historic final days of these young men, we endeavor to tread lightly on the sentiments of the surviving families and others who were impacted by these events. Facts and truth without tact can be hurtful. The Editors very humbly apologize if content on this site causes any such reaction. In the words of Tom Cartwright when he shared sensitive information about the Hiroshima POWs, "I truly hope that no one, especially family, is caused undue renewed grief."