Chapter 4.

At the Bomber Crash Sites

The Crash Sites Crowded with Military Police Personnel and Villagers

It is easy to imagine how astonished Japanese villagers were when an American soldier came down to their village. Some must have been taken aback, while others must have felt aggressive. Some years ago, a book was published by the Ishiuchi Citizen’s Hall, in the suburbs of Hiroshima City. The title is The A-Bombing and the Pacific War.

During the Pacific War (WW II), Ishiuchi Village was assigned the duty of feeding the military horses, and an episode tells how cruel a duty it was for a family whose male head of the house had been conscripted into the military. Another episode was about how people of the village dealt with the war situations, and so on. Several episodes dealt with issues that were rather difficult to speak openly about. One of the personal accounts was titled Shooting Down of an Enemy Plane; the events at that site where the US airmen’s aircraft had crashed were vividly recorded in this book. The crash site was in the muddy rice field, and the wreckage of the aircraft had been scattered all over. Therefore, I made up my mind to visit the author of the article to confirm the details of his story. His name was Mr. Akira Kubota. I walked for several kilometers, climbing up a mountain, and reached the house I wanted to visit. It was a big house, indicating that the family must have a long history in this area. As I had contacted him in advance, I was invited into the Japanese style parlor right away. Displayed on a varnished horizontal shelf in the room, were photos of the family members who had passed away. One was a young man who still had the face of a boy. It was the younger brother of Mr. Kubota. My brother went out on the mission of the kamikaze pilot and was killed in action, he told me in a lowered tone. Before departing on the mission, he flew over the sky of Ishiuchi Village, flew around the house, and repeatedly waved his wings to say good-bye to the family.

That was toward the end of July, 1945. Mr. Kubota then was working at the Japan Steel Mill in the suburbs of Hiroshima as a mobilized student, but it was a holiday so he was at home. As he heard an extraordinary roar of an airplane, he went out to the road. He saw a formation of three bombers, flying low at ease towards the west, coming from the direction of Yamada, which was located to the south-east. Suddenly, behind the formation, he heard the shooting of an anti-aircraft gun and saw the smoke of an exploding shell. They were enemy planes. Eventually, he saw a flash around the horizontal tail of a plane at the rear, which immediately began to lag behind the formation. Soon after, the tail disintegrated, and the plane started to nose-dive down. The shell had hit the plane. Stirred and alert with excitement, he could see something different from the broken pieces of the plane slowly falling. When he stared carefully he could see that it was a parachute, and he could see around two of them. One of them was blown away by the wind and landed. Mr. Kubota hesitated before deciding if he should go search for the crewman or not. He wanted to go but he was concerned that he might be shot and killed. After some thinking, he decided to investigate. As he had not made a bamboo spear, he took a sickle, which he tucked into his belt. He saw others coming, when he passed near the Denchuji Temple he felt encouraged, and continued along a path along the valley stream to the scene. Villagers were seen among the wreckage, looking for something. When Mr. Kubota looked attentively, there were a lot of chocolates, gum and candies on the ground, which the villagers were picking up. The air was full of the unusual smell of gasoline and oil, and machines and tools were scattered around with broken pieces of the airplane. Debris was all over the place. This US airplane was a B-24, and it was hit and shot down by a shell that was fired from the anti-aircraft gun position of Eba district of Hiroshima.

I spoke with as many as fifty-one witnesses of this crash site of the Taloa. I continued with my best efforts to learn the facts about what had happened there.

At the Scene Where the Taloa was Shot Down

Mr. Kiyoshi Suzutani captured one of the American soldiers who parachuted down from the Taloa at Yawata Village, Saeki County, Hiroshima Prefecture (now known as Saeki-ward, Hiroshima City). He belonged to the special Engineer Corps, and was digging a hangar (bunker) for torpedoes at Furue, near the estuary of the Ota River. Mr. Suzutani witnessed a US soldier parachuting down. He hurried to the scene in Yawata Village, which was 3 km away, found the soldier squatting in a coppice (woodcut), dragged him out and captured him. Mr. Suzutani was unarmed, and was carrying no weapons, but mysteriously he had no fear. This soldier had no wounds, and when Mr. Suzutani told him to climb down the hill, he obediently followed. In broken Japanese, he was repeating, “Ohayo, ohayo (Good morning).”

Wreckage of the B-24 Taloa, one of two Liberators that were shot down during a bombing run over the Japanese battleship, the Haruna. The crash site was in Saeki-ward, Hiroshima City, Photo credit: Mr. Akitaka Fujita

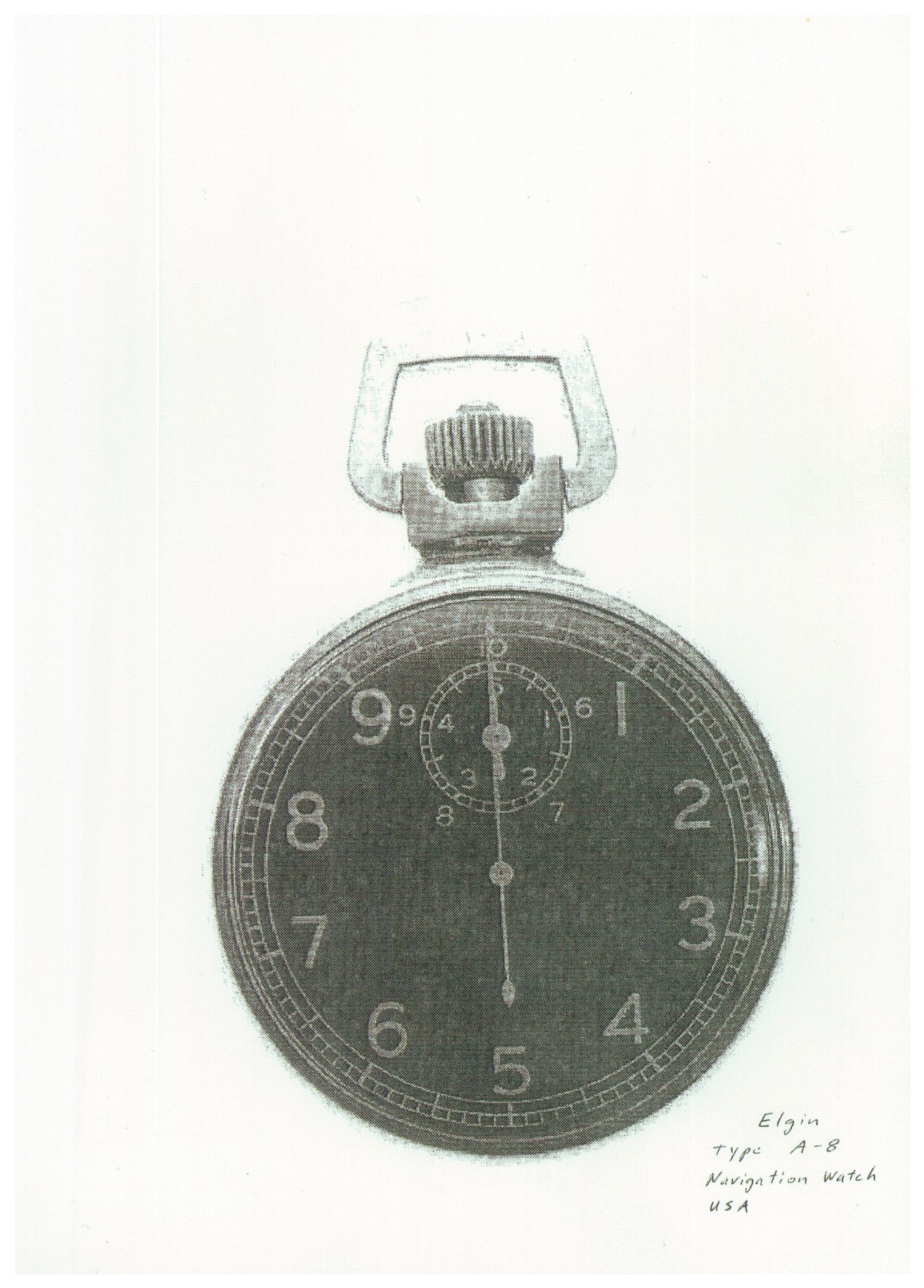

Many people saw the plane that fell in Itsukaichi City. As the American soldier was put on a truck and went down the road people along the road shouted, “Banzai, banzai!”[1] and a whirl of excitement rose. A lot of people rushed to the scene where the plane fell. At first, the wreckage of the plane was roped off, with military police standing on watch around it, prohibiting people entering the roped area. Eventually, both policemen and military policemen left, and the local residents started to take home various remains of the airplane one by one. Among them, was Mr. Masayoshi Kubota, who was a junior high school student. Mr. Kubota found a watch among the wreckage and brought it home. It was not a wristwatch, and looked like a pocket watch. Being an instrument of the navigator, it must have been a personal belonging of 1st Lt. Jack Falls. Later, when I located the bereaved family of 1st Lt. Falls in America, Mr. Kubota asked me to return the pocket watch to the family. The American family, who received the watch I sent, was very glad. At the time of this writing, pieces of the wreckage of the Taloa are preserved in the Irifuneyama Museum of Kure City.

As mentioned above, Walter Piskor, the first to bail out from from the striken Taloa, landed on the roof of a factory at the current West Airport. The students of Hiroshima 2nd Junior High School were watching, having been dispatched to work at the factory as part of the gakuto-doin (mobilization of students) system of Japan’s civilian war effort. Viewed from below, it appeared that high on the roof of the factory a Japanese man who climbed up and a US soldier were grappling in fight. Then the Japanese threw the soldier down. In fact, the American soldier had already died, and the way the Japanese were trying to extract the body from the parachute looked like fighting. The high school students crowded around the soldier, but they were driven away by adults. The corpse was examined by Dr. Katsuo Kusakabe, Director of Mitsubishi Hospital, and was carried to the Kokuzenji Temple in Hiroshima City and was buried there. I have already written about the American serviceman Flanagin, who landed at the estuary of the Ota River, who also was examined and buried in Kokuzenji Temple. After the remains of the two were retrieved by the US Armed Forces, Piskor was buried in a private grave in Connecticut, and Flanagin rests at the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific (Punchbowl Cemetery) in Hawaii[2].

The fall of the Taloa was widely reported by newspapers and was repeatedly broadcast by the radio, after both reports had been censored by the military authorities. The good news was welcome and excited the Japanese people.

Six graves of the soldiers who were went down with the Taloa were dug near the scene of the crash. After the war, they were disinterred and the remains were taken by the US Forces. The task was filmed by the US Armed Forces in color, and should be preserved in the USA.

After the B-24 Taloa was shot down on July 28, 1945, grave markers were built at the crash sites for crew members Marvin, Kirkpatrick, Allison, Bushfield, Johnston and Falls where their bodies were buried. After the end of the war, the US military carried the remains back home. (Photographed by Mr. Akitaka Fujita.)

Editors' note: Shigeaki Mori also located wreckage that was recovered by citizens who lived near the crash site of the Taloa.

The Wreckage of the Lonesome Lady

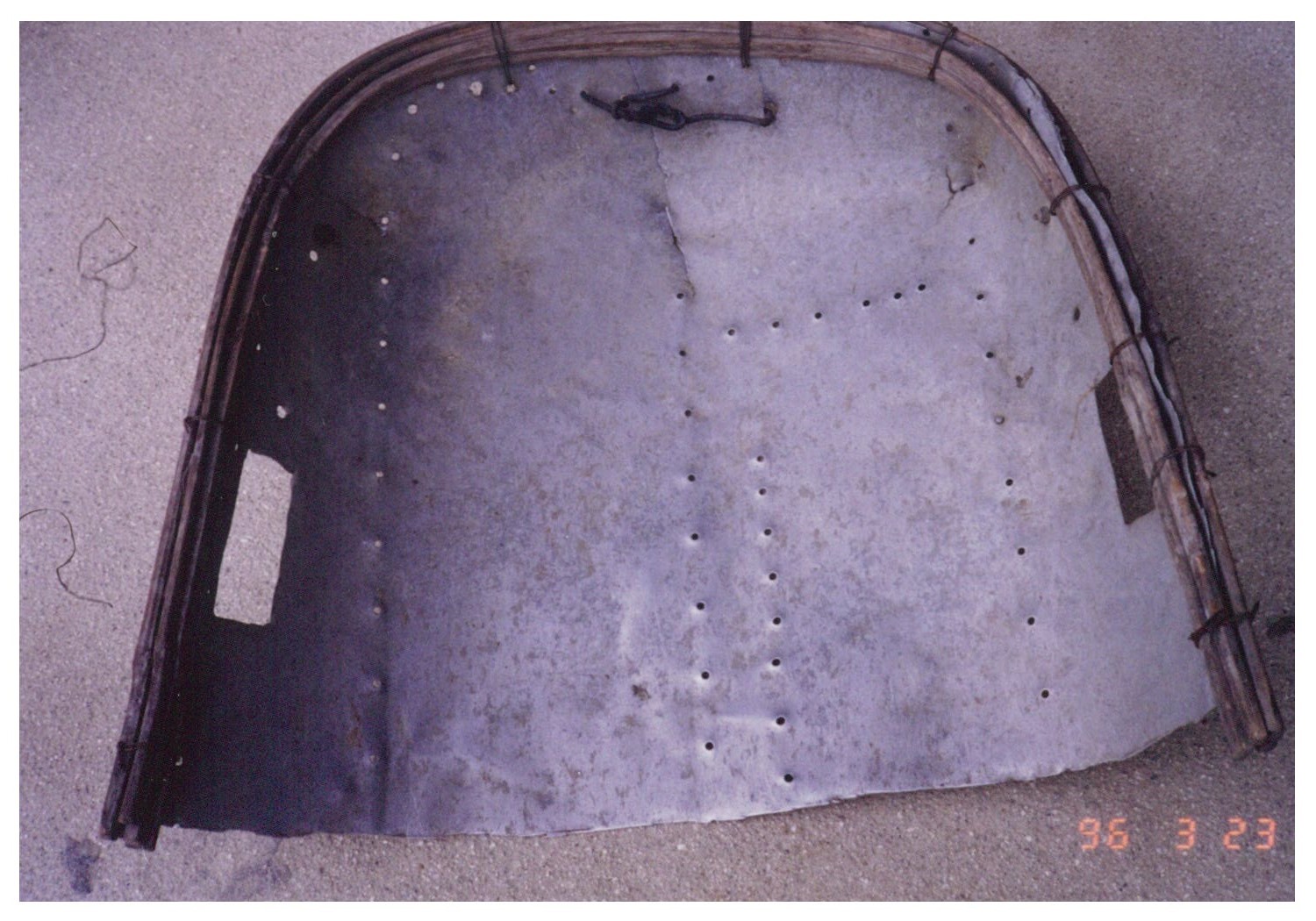

The B24 Lonesome Lady flew out of control from the west, and finally spiraled down, crashing into the foothills above Ikachi, Yamaguchi Prefecture. Cartwright confirmed the direction of approach, which belied the fact that the plane was involved a strike to the east of Ikachi. (Photo courtesy of the author.)

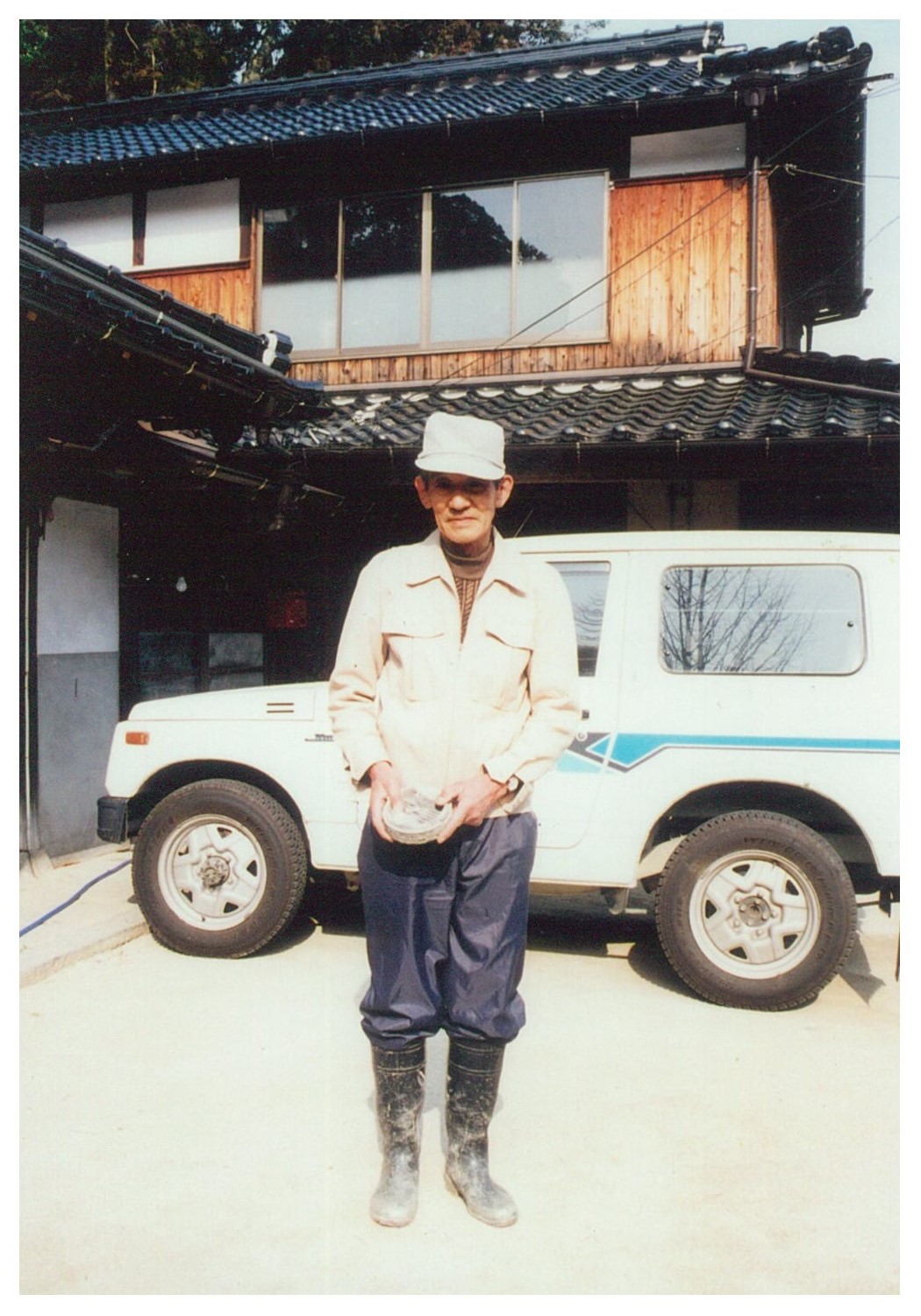

In March, 1996, a resident of the suburbs of Hiroshima called me, inspired by a newspaper article. The headline was A US Soldier Died of Radiation Exposure. He was the 4th American Registered in the Deceased Roster. It reported that I, on behalf of Mr. Francis Ryan, the elder brother of 2nd Lt. James Ryan, submitted a written application to the Hiroshima City Government, and consequently, his name was accepted for entry on the death scroll preserved in the Atomic Bomb Memorial of August 6. 2nd Lt. Ryan was one of the crewmen of the Lonesome Lady. The person who called me was Mr. Takashi Aoki. Mr. Aoki asked me about the possibility of the bomber he read about in the article was the one who fell in his homeland. I listened to his explanation of the approximate spot, and said, it seemed very probable. To confirm this, I asked him to take me to the scene. I had never been to the actual scene of the incident. Mr. Aoki took me by car to the site of the crash. We departed from Hiroshima via Iwakuni, and climbed up the mountain road toward the northwest. Eventually we reached a mountain village in the Chugoku Mountain Range. It was Ikachi Village, Kuga County, Yamaguchi Prefecture.(currently Ikachi, Yanai City). Viewed from the national road through the village, we could see where the plane fell at the foot of a hill. I stepped on the raised footpath between the rice fields, guided by Mr. Aoki. Around 800m from the national road ran a stream about 1m wide, above which we could see terraced rice fields on the slope of the hill, overlooked by a mountain lodge. It was this area where the plane fell, and the wreckage was scattered all around, Mr. Aoki said, pointing to our surroundings. Nodding to his words, I looked, unintentionally, at the stream near my feet. I saw something glittering in the water. When I stepped into the water and picked it up, it was a piece of airplane made of duralumin! Behind me, Mr. Aoki said, “There were thousands of such pieces all around here.” His words made me feel for sure I was standing at the site of the plane crash. Hearing that a mountain fire started at the hill, I stepped onto the upward slope pushing aside the grasses. Mr. Aoki said there could be still some broken pieces of the airplane in that area too. As I removed some fallen leaves, I found another piece, covered with mud. I looked at it with my heart pounding, and wondered if some people might have even larger pieces of debris from the B-24 crash.

This traditional wooden structure is the Public Hall of the Ikachi Village, Kuga County, Yamaguchi Prefecture. As seen here, and as ordered by the GHQ, the wreckage of the Lonesome Lady was gathered and stacked into a large debris pile by villagers in front of the Hall along the national road, around 800m away from the crash site. (Photo courtesy of Mr. Yozo Kudo).

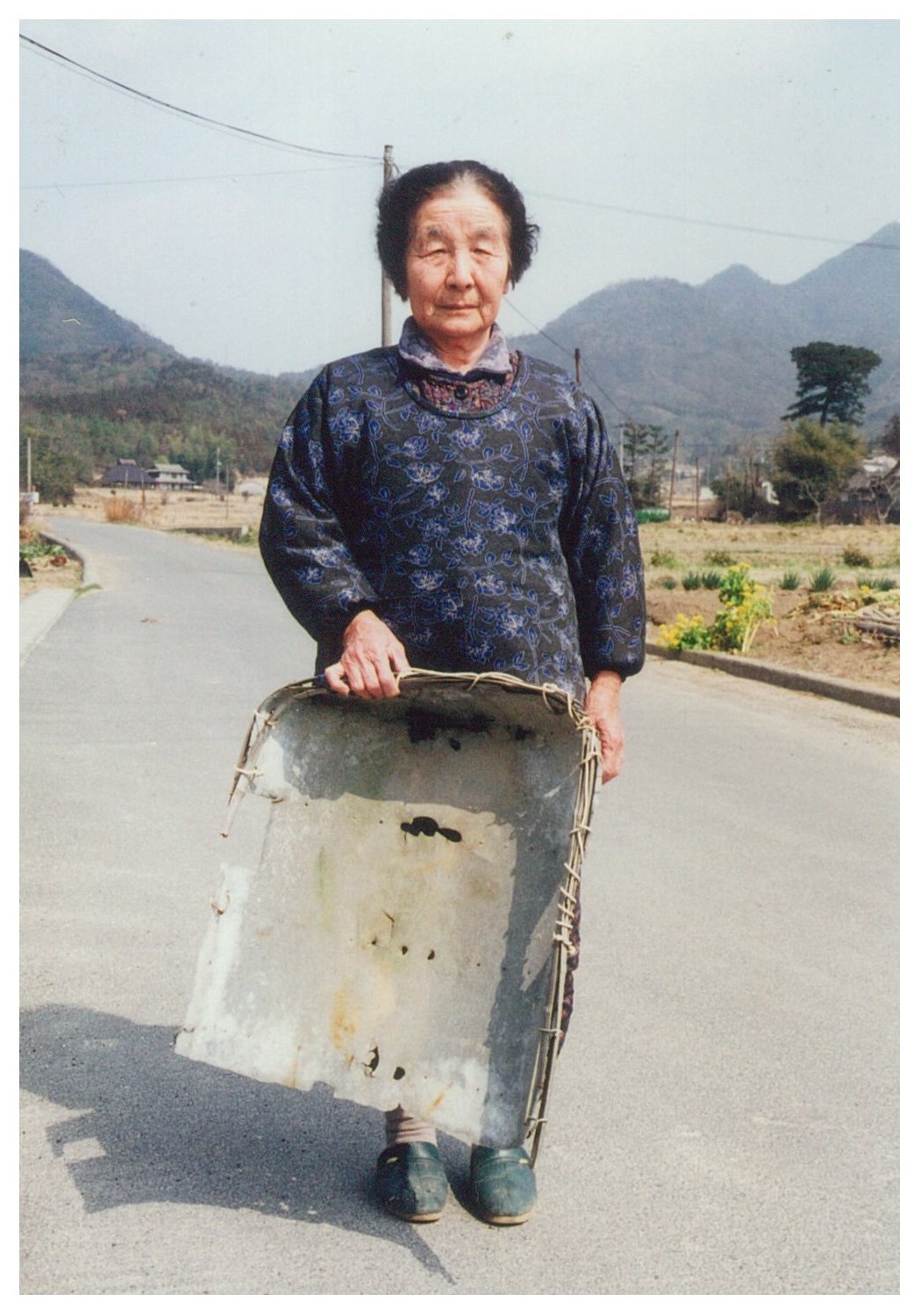

Yes, there was one. The owner was Ms. Yumiko Takenaga, who lived in the area. She had a piece of the plane wreckage made into a frying pan (wok) and a tool, called mi, which was used in farm work. As I went on visiting the villagers, I gradually understood the circumstances in those days.

Mr. Takashi Taniyama, who happened to pass by the site just before the crash, saw such a scene. One of the four engines spiraled down and severed the roof of a shed in two. On the adjacent hill a fuel tank fell and rolled downhill, sprinkling gasoline, and caught fire, causing the whole hill to burn. A house at the foot of the hill was totally destroyed by the fire. On July 28, 1945, the end of the Pacific War was close and almost all the young men of the district had gone to war, leaving only a few behind. It was just the elderly, women and children left behind. All the villagers cooperated in carrying water from the nearby stream, relaying buckets standing in a line, and succeeded to extinguish the fire. Guided by Mr. Aoki, I visited the site after half a century had passed. Because the plane that fell was so big, the local residents thought it was a B-29. Also, as it flew from the west, they never thought it had been shot in the fighting which took place above the sky of Kure Harbor. The unattended Lonesome Lady continued in uncontrolled flight, and then fell, spiraling down. When the airplane crashed, 2nd Lt. Shinichi Fukui of the Military Police and many other military police soldiers hurried to the scene. The Lonesome Lady was equipped with the newest radar, and the Japanese military intended to examine the airplane in detail. However, before the military police arrived at the scene, the villagers had picked up and brought home everything notable and hid them in their barns or above the ceiling of their home.

By the way, when I told Ms. Yumiko Takenaga, who I mentioned already, that I’d like to send the frying pan and mi, which she possessed, to the former pilot of the plane who lived in America, she amiably agreed. Therefore, I sent them overseas. After that occasion, I visited the area many times, and through kind introduction of Mr. Aoki or his mother Mrs. Teruko Fujinaka, I could meet more people who had pieces of the plane. Some gave me the pieces they had, so I sent them to the USA. Eight people offered the pieces they had. Thomas Cartwright was very glad that he received those items, and sent me eight letters of thanks to be forwarded to the people of the village.

winnow

winnow |ˈwinō| verb1 [with object] blow a current of air through (grain) in order to remove the chaff.• remove (chaff) from grain: women winnow the chaff from piles of unhusked rice.

This winnow was fashioned from bamboo and pieces of the wreckage of the Lonesome Lady. Image courtesy of Clarke Abbey.

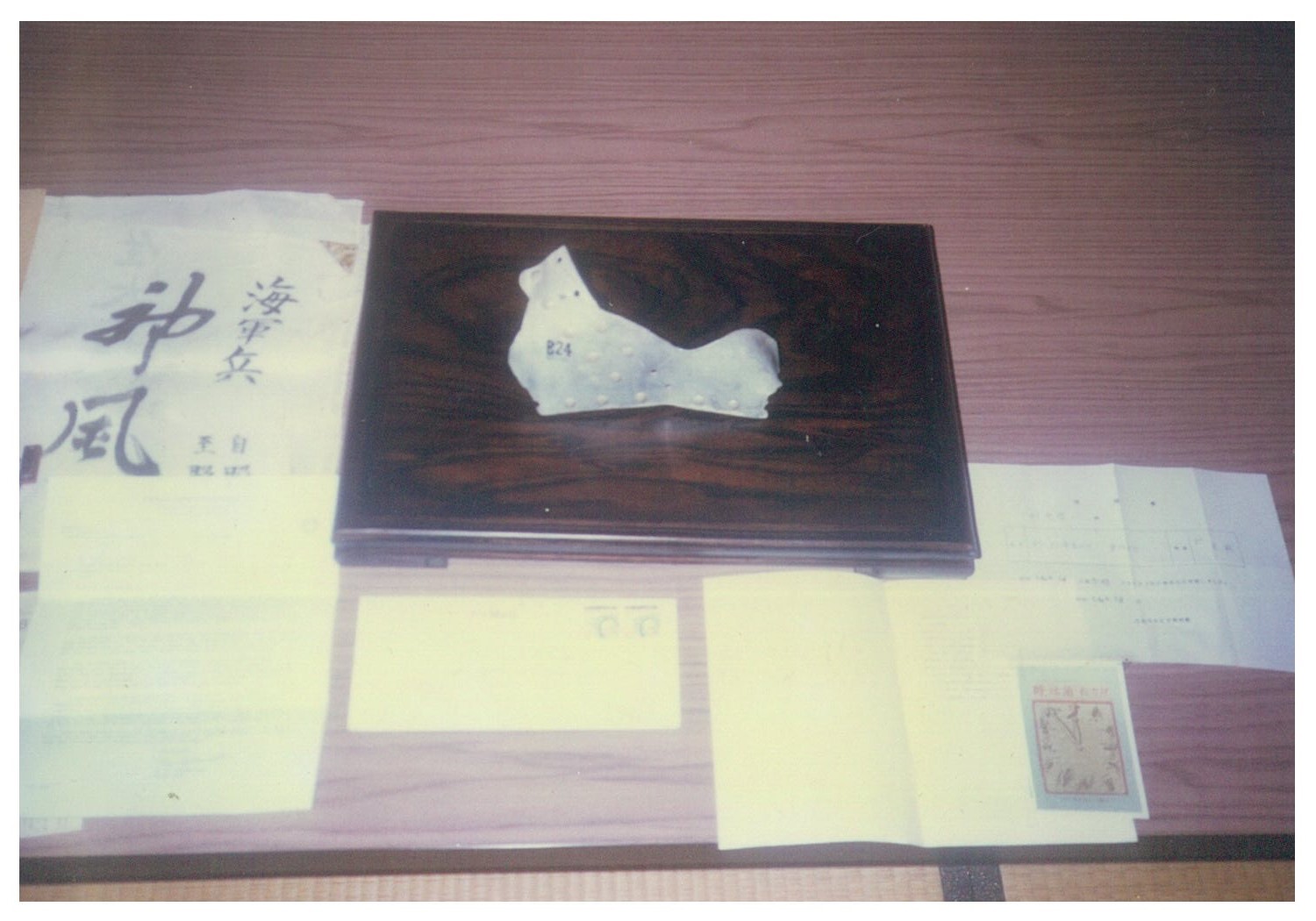

This is the piece of wreckage from the B-24J Lonesome Lady that Keeichi Muranaka found and later sent to the pilot who was shot down, Thomas Cartwright.

After the war, the wreckage of the plane was carried out to the side of the national road, and was piled up in front of a little village hall. One of the pieces was taken and brought home by Mr. Keiichi Muranaka, who was then a teacher of an elementary school of Iwakuni City, Yamaguchi Prefecture, and later Principal of a junior high school. He saw the piled up wreckage of a plane by the road side while on his way to visit a relative from his home in Hizumi, Yanai City. He brought home a duralumin piece he found among the pile, which was more than twenty centimeters long and more than ten centimeters in width. It was early in 1946. In his classes in elementary and junior high schools, he always taught the students how awful war is, showing them this piece of wreckage. Then, still later, through a newspaper article, he happened to learn that the fragment was part of the bomber Lonesome Lady, whose pilot was in America. He considered returning the piece to the pilot, and soon sent it to Thomas Cartwright with a letter. In his letter, he wrote “I hope we will never have such a tragic war again”. Cartwright responded to this letter, enclosing a photo. The photo showed the piece returned by Mr. Muranaka, which was crafted into a plaque.

Dr. Cartwright, former pilot-in-command of the Lonesome Lady, holds the plaque fashioned from a piece of the wreckage from the bomber Lonesome Lady, sent to him by Mr. Keiichi Muranaka. (Courtesy of Dr. Cartwright.) Professor Cartwright was profoundly moved by receiving this fragment of the plane that he commanded as a 21-year-old 2nd Lt. in the US Army Air Force.

Quoted from the Letter of Mr. Cartwright:

On this plaque is set a broken piece of the B-24 Liberator Bomber, the Lonesome Lady, of the US Air Force. This bomber was shot down by the Japanese on July 28, 1945, after bombing the Haruna, a battleship of the Japanese Forces on Kure Bay. After the crew parachuted down, the plane fell in Yamaguchi Prefecture, and seven crew members were captured as POWs. Six of them were in Hiroshima on August 6. Their names were Looper, Ryan, Atkinson, Ellison, Long and Neal. I believe Pedersen died on the day of the fall. All the six men who became POWs in Hiroshima died because of the direct and indirect effect caused by the A-Bomb which was dropped on Hiroshima. Abel was not taken to Hiroshima. Cartwright was originally captured in Hiroshima, but was taken to Tokyo for interrogation from the end of July to the beginning of August, so he survived. Abel survived being taken to Ofuna via, not Hiroshima, but Kure, and survived and returned to the USA as well as Cartwright.

Mr. Keiichi Muranaka found a broken piece of the Lonesome Lady, near the impact site. By an unexpected coincidence, he had been a gunner of the battleship, the Ise, in the Battle of the Sea and Sky on July 2, 1945. In 1985, he sent Cartwright, who had been the captain of the Lonesome Lady, the piece which he had owned, with the following words: “I’ve had this, a reminder of the sorrowful experiences of the period, which we shared as horrible days of our history; I’m giving it to you now. Through sharing those memories, we will be able to preserve peace. That is our responsibility to do so.”

This plaque has been made, praying for the peaceful rest of the crew members of the Lonesome Lady, who died in Hiroshima and Yamaguchi. With gratitude from the bottom of my heart that Mr. Keiichi Muranaka returned this broken piece of the plane to me, I accepted it. I will also engrave in my heart the spirit of peace that Mr. Muranaka had stated. This is not just a curved broken piece of a bomber that had fallen, but rather a symbol of our remorse for that war and our hope for peace. Dr. Mac Prescott[3] himself hand-crafted this plaque made of Pecan wood, which is the state tree of Texas.

Wreckage of the Lonesome Lady also is preserved in the Yamato Museum:

[1] “Bonzai” could be understood to mean “hurray” in this context.

[2] http://www.pacificwrecks.com/cemetery/hawaii_punchbowl.html Flanagin (Air Medal & 5 Oak leaf clusters/purple heart) died on July 28, 1945 and is buried at Plot P Grave 1113.

[3] The fabrication of a plaque for the piece of wreckage was a gift from Dr. Prescott, who was Dean of Science and Provost at Texas A&M University and the Father-in-law to Dr. Thomas Cartwright’s daughter, Susan.